In music, no American state seems to inspire more than California. There’s the sundry topography, the relentless sunshine. It’s the edge of the continent. In poetry and prose, California is opportunity. It’s reinvention. It’s the opportunity for reinvention. And in song, from the Bakersfield sound to West Coast jazz, Laurel Canyon folk to yacht rock and G-Funk, California has consistently been a place where musical vernacular is dreamed up, reimagined and redefined.

Florida, on the other hand, hasn’t historically offered much in the way of metaphorical shorthand or easily identifiable sonic touchstones (disregarding the late Jimmy Buffett’s country-adjacent Gulf & Western sound, which wrangles and subdues various American-roots styles in an island-time sleeper hold).

Though he now lives in California, the multi-instrumentalist and multi-disciplinary artist Jacob Cummings grew up on Florida’s central coast and spent the majority of his formative years near the Atlantic Ocean. Across collaborations with his partner, the singer-songwriter Laney Tripp, and as a contributor to a growing list of projects headed up by other musicians, Cummings has, for the last few years, been cultivating a musical language that’s rooted in the Sunshine State.

Released in November, Cummings debut solo full-length, Southern & Enlightened, is an 11-song collection of ambient-leaning, experimentally-inclined indie folk. Drawing inspiration from his experiences growing up in New Smyrna Beach, and composed largely during a months-long stay in Juno Beach, the album is Cummings most articulate expression of his regionally-inspired musical dialect to date. It’s also a deeply personal collection that draws sonic originality from the waterborne region in which he grew up – a place of unique beauty and fragile biodiversity imminently threatened by coastal erosion, climate change and unfettered development – and his own familial upheaval – his grandmother’s death, a growing estrangement from his father – to tap into universal meditations on mortality and impermanence.

“I feel like, inevitably, my environment rubbed off on the music,” the now-Los-Angeles-based Cummings told me during a recent phone conversation. “I think, on the surface, that comes out in this calming, easy-going, coastal listen. But in the process of making the more lyrical songs, and singing, I’m trying to process difficulties in the family dynamic and tie things up or find closure.”

Cummings studied classical saxophone at the University of North Florida. And many of the musical friends and collaborators he met in Jacksonville – including Corey Kilgannon, Taylor Neal (Teal Peel), Brian Lester (Teal Peel, Bobby Kid) and Landon Gay (Howdy), among others – contributed to Southern & Enlightened. “I’m super fond of where I grew up,” he told me. “I think over the years, I’ve made it a big part of my creative or artistic identity.”

Like his previous project with Tripp, 2023’s Cedar Island Songs, Southern & Enlightened is a serene listen, conjuring images of where sand meets the sea. And like Cedar Island, Southern & Enlightened’s beaches offer refuge and solace, rather than an opportunity for levity or debauchery. Over simple progressions of often just two chords, Cummings imbues his songs with an estuary of atmospherics – synths, pedal steel, sax, et al.– and alternates between instrumentals and vocal-led tracks across nearly the entirety of the album. Rather than narration, Cummings’ vocals, when they do appear, provide emotive brush strokes to songs that are each their own abstract painting. With all its conjuring up of imagery and sense of place, Southern & Enlightened feels closer to a fine-art installation, something for which you might plop down on a gallery bench to devote your undivided attention.

The album opens with “If You Can Hear Me, Mom,” a reverent instrumental featuring looping keyboard plunks and watercolor smears of ambient synths and saxophone tucked neatly into the mix. We first hear Cummings’ voice on “Incarnations,” a pleasant, acoustic forward number that, between ruminations on transience, resolves with the phrase “you don’t have to stay forever.” The subaqueous instrumental “Run Away,” leads into “Joan,” perhaps the closest any song on the album comes to having a conventional groove. Cummings includes a truly distinctive cover of Randy Travis’ “Forever & Ever, Amen” as the album’s penultimate track, before the spacious and a lyrically concise closer, “Love in the End.”

Thematically, Southern & Enlightened tracks the process of processing. There are the more quiet, wordless moments of contemplation, of working through stuff while having little to say about any of it. Then there are the times where it all comes rushing out; occasionally with clarity or concision.

“I didn’t feel a need to force any lyrics or singing on any of the songs,” Cummings says of the album. “The ones that did end up with lyrics just felt like they arose naturally, in the moment. I was kind of just letting things pour out.”

Along with the album, Cummings created a short film for the project. I recently talked to him about the making of the album, drawing inspiration from Florida and how his work as a visual artist influences his music and vice versa. The following conversation has been edited for content and clarity.

Let’s get right into the title: Southern & Enlightened. Some might see the inclusion of the ampersand and the word “Enlightened” as some kind of commentary on the South. Of course, we often read too much into the titles artists apply to their work. Where’d that title come from?

It saw it as an overarchingly cool combination of words. I’ve always liked Cocteau Twins’ Heaven or Las Vegas. I wanted a dichotomy. It’s almost ironic how we think of those two things – southern and enlightened – as opposites. So it’s funny for me to pair them together. I had the title in my head early in the process of making the album. It sort of stems from me thinking about people who I’ve had conversations with that aren’t lining up and I have to come around or work hard to come to an understanding and try my best to resist any judgment. I’d like to understand where they’re coming from or where they derive their fears.

So you drew inspiration for the album partly from memories of growing up in New Smyrna Beach. Are you fond of where you grew up? What about that place finds its way into your work?

I’m super fond of where I grew up. I think over the years, I’ve made it a big part of my creative or artistic identity. And I’m almost hoping that this project is kind of the end of that. After spending many years in Los Angeles, it’s me coming full circle and thinking about the unique people and environments that are inherent to coastal Florida.

A big part of it is my dad just being a total character. He moved down from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to get away from his life up there and became, what I see as, the epitome of a ‘70s Florida guy. He’s had 13 Volkswagen buses over his life. He got us into surfing. It’s like the dudes that hang out on the boardwalk in every coastal Florida town. My lens of New Smyrna, I can’t help but feel is built around him. In the good ways, that’s inspirational; you know, try your best to live this kind of Bob Marley-esque life, ride your bike on the beach, check the waves, go to Clancy’s Cantina in the evening and see a couple of your buddies, roast those Orlando people.

And during the making of the record, you spent some time back home. Tell me about what you were up to and how that influenced your writing.

My grandma passed away and she had this great house. She was there for 50 years. It’s where my mom grew up. It was on this canal and had this old terrazzo floor, mango tree in the backyard. But when she passed away, the consensus among the family was to sell the house. And in cities like Juno Beach, there’s just no chance that this old house would, whoever bought it, remain intact. I was assuming some investor would buy it and demolish it. So I went there really wanting to make amends with the house. I cleared my schedule and spent a month-and-a-half there with the goal of focussing on myself. I was reading and running every day and trying to meditate every evening.

“I didn’t feel a need to force any lyrics or singing on any of the songs. The ones that did end up with lyrics just felt like they arose naturally, in the moment. I was kind of just letting things pour out.”

With that, I brought like six checked bags filled with music gear. I thought there’d be no better time to work on a music project. I feel like inevitably, my environment rubbed off on the music. I think, on the surface, that comes out in this calming, easy-going, coastal listen. But in the process of making the more lyrical songs, and singing, I’m trying to process difficulties in the family dynamic and tie things up or find closure. There was a lot of turmoil with my dad showing up and I can’t help but bring up this album having a lot to do with me processing my relationship with my dad or almost accepting his huge shortcomings or learning to be OK with the fact that the dad that I grew up with will never be the same.

Yeah, that makes sense. The lyrics across the album often come back to thoughts on mortality, human connection. Those topics keep coming up. And the tracks kind of bounce between instrumental songs and songs with lyrics. When you’re writing or composing, how do you decide which songs get lyrics?

It was a pretty fluid process. The songs that have lyrics were just melodies that I was humming through voice memos over the years. When I surfaced this project at my grandma’s house, I went through hundreds of those voice memos and picked ones that resonated with me. Some had some stream-of-consciousness lyrics. But most were just me humming. I didn’t feel a need to force any lyrics or singing on any of the songs. The ones that did end up with lyrics just felt like they arose naturally, in the moment. I was kind of just letting things pour out. I was just thinking about everything that happened in that house and making amends with that house going away. In the midst of that, I was thinking about my mom passing away and my dad having a pretty tough relationship with alcohol. It’s a kind of closing of a chapter with him. Hopefully, in more subtle ways these songs come off as something cathartic.

What does Florida sound like to you?

Florida to me sounds like a Saturday morning marching band festival in the fall after a long night of playing the “Final Countdown” or “Sweet Caroline” in the stands of a football game. Or 2000’s rock blaring from a cheap PA system at a surf contest. Or Lil Wayne’s “6 foot 7 foot” playing in the school bus from somebody’s iPod Nano. Or a Sunday morning worship team playing a Chris Tomlin or Steven Curtis Chapman song. Or any white reggae band. To me right now, the Grateful Dead bridges this gap between country and island-y that really makes the most sense to listen to in Florida. Jimmy Buffett almost feels the same way to me; just less jammy.

As a multidisciplinary artist, have you identified ways in which your work, say in photography or videography, finds its way into your music, whether through imagery you’re trying to convey with lyrics or a setting that inspires a collection of sounds?

For a lot of these songs, I had an idea for a video concept in my head while I was making them and that eventually steered the film project that I did for the album. But, in a different way – and I was just thinking about this yesterday – I often, maybe equal to music, surround myself with photographers and videographers or visual artists, and the idea of approaching music from a more visual-arts perspective, and vice versa, is exciting to me. That sounds vague but I think I would like to approach both as an outsider moving forward. Because I went to music school and was in band, there was a big emphasis on performing very technically. Like most band kids I’ve been very insecure about my talents. It took a while to learn that it was much more exciting for me to find my own voice and specific sounds that resonate with me. With this project, there was no feeling of “How can I do something impressive or technical?” A lot of the songs are just two chords going back and forth, in an attempt to be really meditative or put you in a different mood.

Your work with your partner, Laney Tripp, is built on collaboration. Tell me about the choice to do a solo album.

The Laney project is a big part of my life and something that I feel really passionate about. Through various projects over the years, I’ve learned to not let my own creative opinions dictate a project or impede on other people’s visions for the project. That’s a hard thing still for me to come to grips with. So the idea of approaching a project where I have full creative freedom was very exciting for me. It was a bit of a rebellion. Most of my work, being for other people, whether photo or video, I’m working in the service of other people’s things. I say that, but I think I’ve also realized that it can sometimes be better to have someone to report to and not to be in charge of all creative decisions. I like the idea of this whole project being a science experiment; learning from the process.

You and Laney went to Vermont and worked with Benny Yurco for Cedar Island Songs. He’s a well-known producer and multi-instrumentalist. Did you glean anything about production or songwriting from him that was particularly helpful to you in making your record?

His 2020 album [You Are My Dreams] was a huge inspiration for me. He’s a great example of blending instrumental songs with singing as kind of brush strokes. Michael Nau was there too. He’s been one of my favorite artists for years. Everyone we worked with on Cedar Island, it was such a magical experience. But after recording Laney’s album just us two this whole year, the idea of having someone like Benny again to kind of help facilitate the whole thing seems really exciting. Working with him was another driving force in encouraging me to really do something on my own. It was a boost of confidence, I think – these people I respect, dig what we’re doing.

How did the Randy Travis song find its way onto the album? I mean, it’s a cool song.

It is a cool song. It’s really not something that’s in my wheelhouse. I like doing covers that fall way outside of my world. I went into the whole recording time wanting to try something like that. I think it might have been the first song I recorded vocals for. Just knowing that it’s not my song and I can still sing on it, was helpful. I didn’t grow up listening to country at all. But Laney’s family did. And so I’ve been listening to a lot of ‘90s country songs over the years now. It’s very easy listening. And this song was Laney’s parents’ wedding song which just adds a level of emotion to it for me. I don’t think Laney even knew I’d put that on there. I didn’t want to share anything from the album with her until it was fully complete. And so it was an exciting idea for me to have her hear that in the midst of listening to the album for the first time.

Southern & Enlightened is available on all streaming platforms. Limited-edition vinyl copies of the album can be purchased via Bandcamp here.

Mr. Al Pete and Notsucal Release Their Latest Collab, ‘G4.5’

Dinner Party, Tom Misch and More from the Neighborhood with Mr. Al Pete

An Ultra-Chill Playlist from the Latest Episode of Electro Lounge

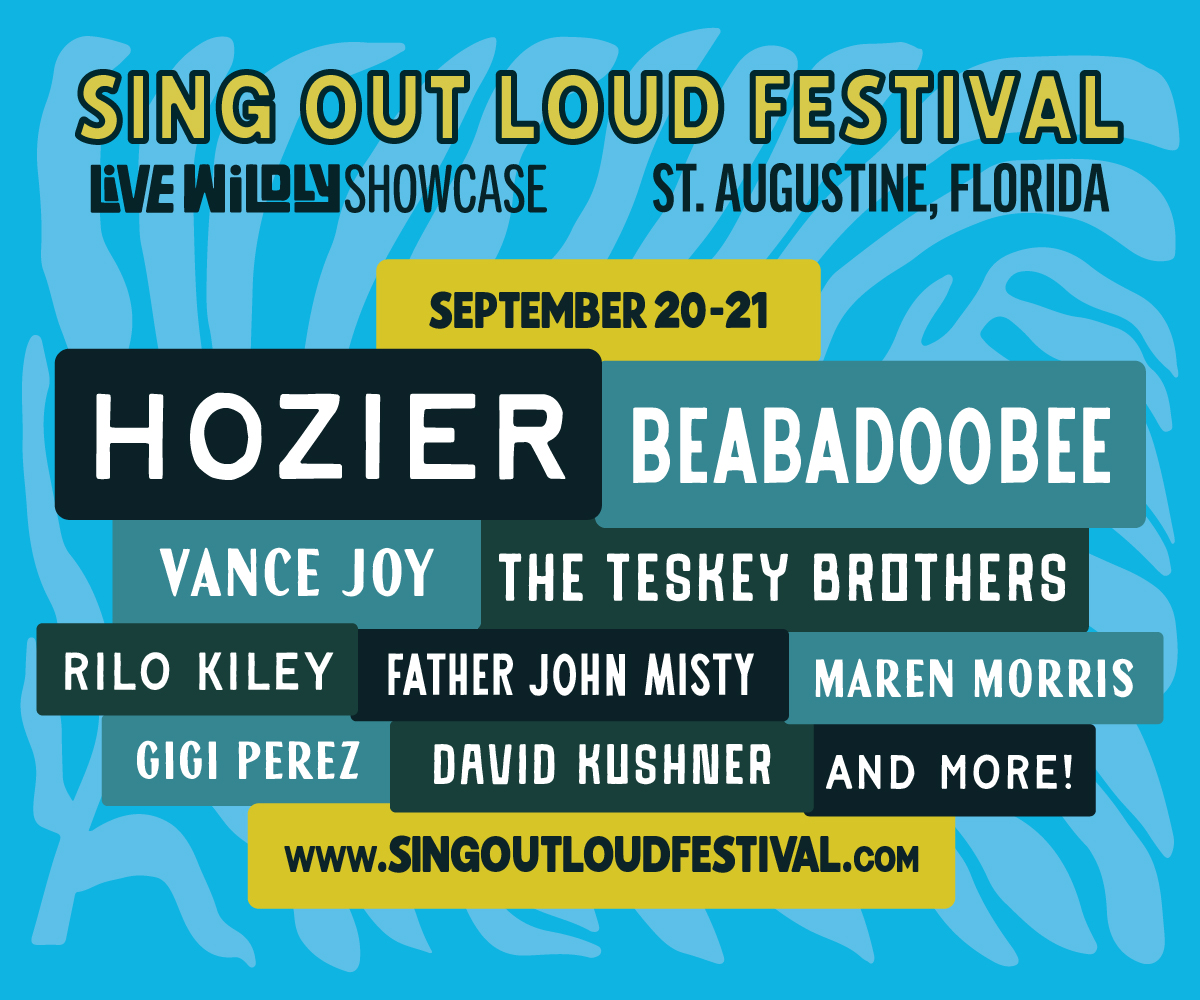

Sing Out Loud Festival Returns With Hozier, Beabadoobee, Father John Misty, Vance Joy and More

Chicago Alt-Country Faves Wilco Return to St. Augustine with Indie-Folk Great Waxahatchee

Looking for an Alternative to Spotify? Consider Hopping on the band(camp) Wagon

Khruangbin to Bring ‘A LA SALA’ Tour to St. Augustine in April

Perfume Genius, Flipturn, Tamino + Mitski and 6 New Songs to Stream

Song of the Day | “all tied up” by Glixen