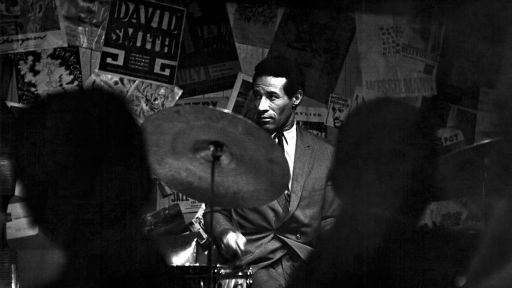

When Max Roach died in 2007 at age 83, the iconoclastic musician had truly lived a life that beat to the tune of a different drum.

Roach seemed to move upstream, regardless of the tides. He was an early adherent to the DIY indie-ethos. While still in his twenties, in 1952 Roach and Charles Mingus founded Debut Records, after the pair were disgusted by the treatment of major labels towards jazz artists. In 1988, Roach was ultimately the first jazz musician to receive a MacArthur Fellowship “genius award.”

This sort of eventual acceptance by the cultural elite seemed like a byproduct of Roach’s fiery spirit. He aimed his orbit into opportunity and was fearless in locking into his chosen trajectory: integrity was the crucial element, success was an arbitrary byproduct out of one’s control.

In the opening moments of Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes, the iconoclastic drummer is asked: “Do you consider this music as a weapon?”

As seen in the grainy, black-and-white interview clip, Roach pauses for a moment and then responds.

“You mean as a weapon against discrimination and things like that?” he says. “Sometimes, the music is used to make people feel happy and joy. But on some occasions, we do use the music as a weapon against man’s inhumanity towards man.”

Over the course of the American Masters documentary’s 80-minutes, The Drum Also Waltzes, shows Roach both rhapsodizing and weaponizing through music.

Directed by Sam Pollard and Ben Shapiro, the film boasts exclusive video and audio interviews with Roach. In 1987, Pollard began filming Roach and did so until the drummer’s death twenty years later. In that same time, Shapiro was also recording lengthy audio interviews with Roach. Featuring intimate anecdotes and live performances, newsreel footage, rare concerts, photographs, and even home movies, The Drum Also Waltzes offers a comprehensive understanding of Roach’s place and influence in 20th-century music and art.

A key takeaway from the film is the complexity of Roach as a person. Roach spent much of his childhood at matinee jazz concerts in New York City. A self-taught player, when he was 13-years old Roach was gifted a drum kit by his father. In one clip, Roach describes waking up in the morning and simply sitting at the drums and thinking about playing. By his peers and family, Roach is remembered as a loving and doting father, a dapper dresser and spiritual seeker, even a capricious bandleader who (like his friend and eventual creative partner, Charles Mingus) would chide and threaten his players during live performances for some real or imagined transgression.

Roach’s involvement in post WWII music with bebop and hard bop (in particular his crucial work Charlie Parker and later with trumpeter Clifford Brown) is given rightful emphasis. Concurrent with the development of jazz music was the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement. From 1962 to 1970, Roach was married to singer-actress Abbey Lincoln. Already successful on stage and in movies, Lincoln was the perfect foil for Roach: determined, fearless and a political activist. In the film, Lincoln describes their pairing as “show biz meets art,” her non-nonsense feminism matching with his restless, seeking spirit. Their 1960 release We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite laid the thematic and musical groundwork for the protest radical and free jazz that would drive subsequent 1960s Black culture and music.

Roach didn’t feel that the term “jazz” was the proper nomenclature for African-American instrumental music. His own creative choices played this out.

In the late ‘60s, after feeling that percussion was getting short shrift as a respectable instrument, Roach began performing solo 90-minute drum concerts as well as onstage “battles” with fellow drummers.

Unlike many of his bop-era peers, Roach was energized by the avant-garde developments in jazz. He worked with “free” players including Cecil Taylor and Anthony Braxton and a clip from the late 1970s in the documentary shows Roach and his percussion-only ensemble M’Boom in concert, improvising on a piece that essentially emulated the movements of the weather.

Unsurprisingly, Roach was involved early in the NYC hip-hop community, with additional footage showing him working with Fab Five Freddy and DJs at a concert in the ‘80s at The Kitchen in Manhattan.

The Drum Also Waltzes is rich with interview footage of Roach’s family and surviving musical and artist cohorts. Musicians including Abdullah Ibrahim, Randy Weston, Sonny Rollins, Harry Belafonte, Jimmy Heath, Charles Tolliver (a Jacksonville native), Dee Dee Bridgewater, and Julian Priester all offer up revealing anecdotes about Roach that help the viewer get a greater overall sense of his being.

The Drum Also Waltzes closes at Roach’s funeral. Thousands attended his service at NYC’s Riverside Church, and the film offers footage of Maya Angelou eulogizing her friend and musical ally. Roach had once told his son Daryl Keith Roach, “If I didn’t pick up the drums, I would have picked up a gun.” Thankfully, Max Roach chose the higher aspect of music and being. The Drum Also Waltzes is a worthy celebration of his life and music.

American Masters Max Roach: Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes airs at 9 p.m. on Friday, October 6 on WJCT-TV JaxPBS and will be available to stream on Jax PBS Passport. For more info, click here.

Mr. Al Pete and Notsucal Release Their Latest Collab, ‘G4.5’

Dinner Party, Tom Misch and More from the Neighborhood with Mr. Al Pete

An Ultra-Chill Playlist from the Latest Episode of Electro Lounge

Sing Out Loud Festival Returns With Hozier, Beabadoobee, Father John Misty, Vance Joy and More

Chicago Alt-Country Faves Wilco Return to St. Augustine with Indie-Folk Great Waxahatchee

Looking for an Alternative to Spotify? Consider Hopping on the band(camp) Wagon

Khruangbin to Bring ‘A LA SALA’ Tour to St. Augustine in April

Perfume Genius, Flipturn, Tamino + Mitski and 6 New Songs to Stream

Song of the Day | “all tied up” by Glixen

Lucy Dacus, Babe Rainbow, Pigeon Pit and 7 New Songs to Stream

JME Live Music Calendar

Want more live music? We got you…