The pandemic and its subsequent lockdown has forced many people into a self-reflective space. For Florence Welch, the frontwoman of the Grammy-nominated band Florence + the Machine, this moment of solitude came with an intense period of personal deliberation over her seemingly fractured desires. Questions about how to balance motherhood with the bodily experience of being a performer left her with a painful type of frustration. To work through it, she took to the studio and put all of these complexities into her latest record for Florence + the Machine, Dance Fever.

In this interview from Weekend All Things Considered, Welch sat down with NPR’s Michel Martin to talk about her creative process for her latest record, the struggles she feels tearing her between motherhood and performing and the influences behind two of the songs on Dance Fever.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Listen to the audio version above.

Michel Martin, Weekend All Things Considered: This is your first album since 2018. You were working on the new album, but now releasing it and working on it in a very different time than you anticipated when you started. Do you think that it’s different from what you would have said … if you had worked on it the way you’d intended?

Florence Welch: I had said at the end of [2018’s] High as Hope, I’m going to stop, I’m going to settle down. I need to stay still because touring is hard and putting yourself out there, even in records, is hard and it doesn’t get any easier. You’d think you’d get used to it, but the more you give and the harder it kind of gets. I was like, I need to take a really big break.

And I did not. It was like the album kind of came to me in a flood and it was like a fever. It was like, you can try and settle and not write, or you can get carried away in this fever of songs. And I really did. And the album became about that feeling, the beginning of it, of being sort of dragged away by your own creativity — from stability, from home, from more domestic pursuits. I felt like I went to New York to make it in this kind of fever of creativity that I was already questioning. I was already like, oh, is this a good idea? But I’m going to do it anyway because it feels so good in the moment.

I need to play [your song] “The King.” Humans have all kinds of different feelings, but there are many people out here, particularly people who identify as women, who will hear those words and will say “Yes? Yes!” At the top of the song you sing, “We argue in the kitchen about whether to have children / About the world ending and the scale of my ambition / The very thing you’re best at is the thing that hurts the most.”

And “How much is art really worth / Because the very thing you’re best at / Is the thing that hurts the most.” It just seems like that’s the summation of my life. And also the conflict of being in a nontraditional role. It’s the stuff that I just never thought about going in as a young woman into making music. It wasn’t like these fears about what am I sacrificing or what other avenues am I missing out on by doggedly pursuing the thing that I’ve loved the most.

I never dreamed of marriage or children. I just thought it was something that would happen. Like, I’ll focus on the work, and that’s something that will probably just happen. I turned 35, and then it became the time to book tours and write again. That was the moment when I realized that for me, the next five years in terms of having a family and making those decisions, that time was becoming more and more precious and pressured.

Did you intend what I hear, which is rage?

I’m so angry. I think my performances are so bodily. They’re so entrenched in my body and I think there are a lot of ways that you can make it work. For me, it definitely felt like I would have to choose, depending on how I wanted to use my body for the next couple of years. And the rage was so acute. It was frustration as well. Just the frustration, which I think is the scream at the end of it. I think a reading of this song would be to oversimplify it, to be like she’s against these things. I am not a mother, I’m not a bride. And the rage is not that I’m against them, it’s the rage that actually, I feel completely split. I feel like I’m being torn in two.

I think a lot of my work as a person, not just on stage, is to find a way to bring my creativity and the more grounded side of me that does want stability and glimpses of normality wherever I can find them. I think it’s been a gradual work for me, especially since getting sober, of trying to bring the opposing sides of myself together. And I think this might be the last hurdle. For me, it’s also going to be accepting change and letting go of control. I have been the architect of my creativity and my life in such a specific and obsessive way. And it feels like handing yourself over to motherhood is a total letting go of control. I’m slowly trying to come to terms with what that means for a perfectionist obsessive who’s controlled every part of their creative life to the nth degree.

Let me ask you about one more song on this album, which is “Choreomania.” The song takes its title from the dancing mania that swept Europe in the Middle Ages during outbreaks of the plague, where people literally danced until they collapsed from exhaustion — clearly making the connection with the current moment. But how did you hear about this? Did they teach this in high school in England?

No, no. I was told about it by a friend, actually. My friend is a poet, and they had written a poem about it that I’m in. But they transferred the dancing plague into current day Berlin. And it would be me dancing in a gay nightclub in Berlin with Patti Smith and Kate Bush. I was like, “This is amazing!”

They told me about this dancing plague and I went down such a rabbit hole with it. There was one specific outbreak in Strasbourg where 400 women danced themselves to death. What I found so fascinating about it is they have so many theories as to why it happened. One of them, which I found really interesting, was that it could have been psychological because of stress, because of all the other plagues that were happening, because of how hard life was in the Middle Ages. It was like a psychological phenomenon, and I just really related to [it].

I understand that you shot the videos for this album in Kyiv before the war. You dedicated the video for “Free” to “The spirit, creativity and perseverance of our brave Ukrainian friends.” It’s such an emotional, difficult and terrible time for so many people. What gave you the idea and have you heard from any of the people you work with there?

[Director] Autumn de Wilde, Kyiv was like her second home to shoot. We shot there in 2021 in November. She was like, “There’s such great crews out there and they have amazing special effects teams” and we knew we wanted to make this epic. Autumn was just like, “I have got an amazing team in Kyiv. Do you want to go to the Ukraine?” I was like, “Oh, I would love to.” We went out there and just spent time. It’s hard to imagine that there [were] kind of rumblings. We just had the most amazing time, and there was no sense of just how much horror was around the corner. And — I’m so sorry — it’s so hard to talk about it without crying.You can cry. A lot of us have cried.

When the war broke out, we just got in touch to make sure everything and everybody was okay. I think everyone’s okay so far. And our two dancers that danced in [“Heaven Is Here“] … one of them is now in England and I’m hoping that I’m going to get to see her, and one of them is now in Amsterdam. Those videos … they are my favorite videos ever made. We couldn’t have made any of them without those crews and those people. It’s really hard to talk about because it’s a feeling I don’t even know how to put into words. It’s still a bit of a shock.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))

Mr. Al Pete and Notsucal Release Their Latest Collab, ‘G4.5’

Dinner Party, Tom Misch and More from the Neighborhood with Mr. Al Pete

An Ultra-Chill Playlist from the Latest Episode of Electro Lounge

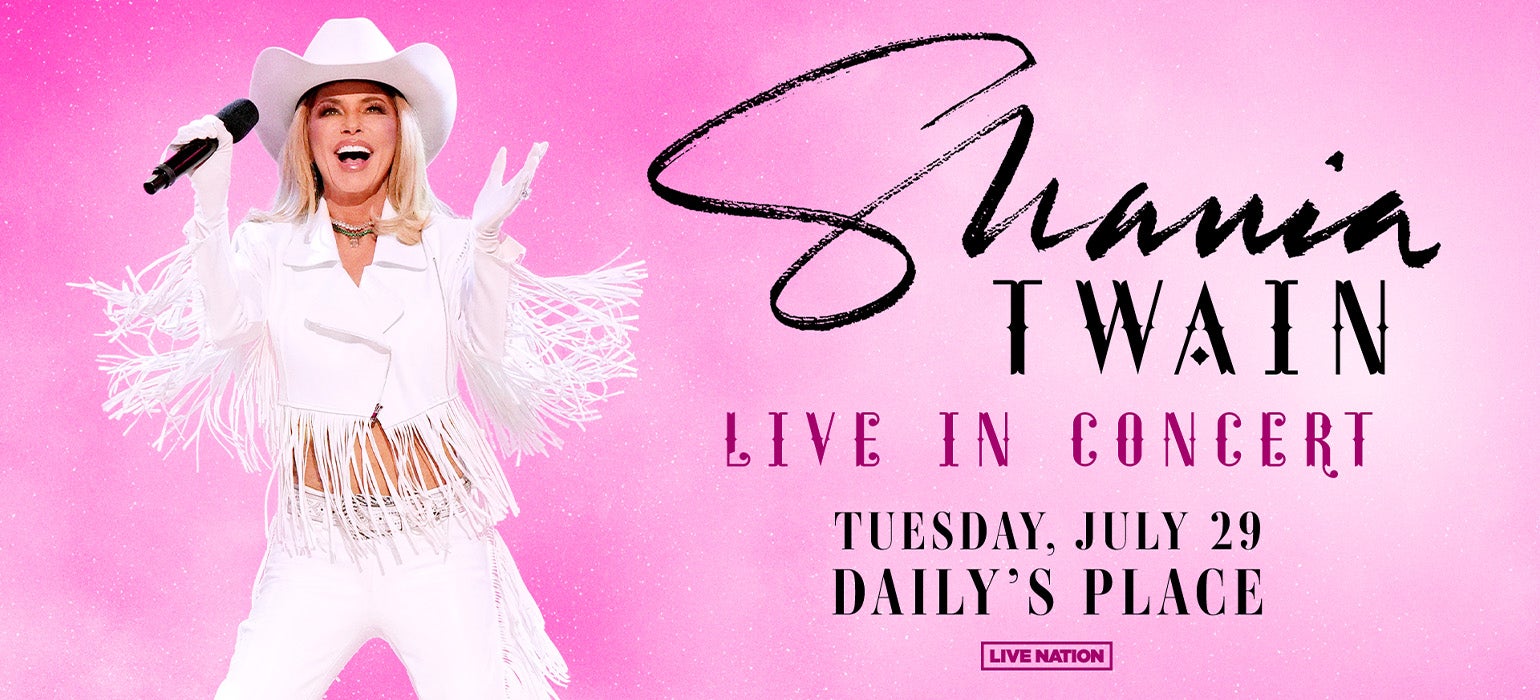

Sing Out Loud Festival Returns With Hozier, Beabadoobee, Father John Misty, Vance Joy and More

Chicago Alt-Country Faves Wilco Return to St. Augustine with Indie-Folk Great Waxahatchee

Looking for an Alternative to Spotify? Consider Hopping on the band(camp) Wagon

Khruangbin to Bring ‘A LA SALA’ Tour to St. Augustine in April

Perfume Genius, Flipturn, Tamino + Mitski and 6 New Songs to Stream

Song of the Day | “all tied up” by Glixen

Lucy Dacus, Babe Rainbow, Pigeon Pit and 7 New Songs to Stream

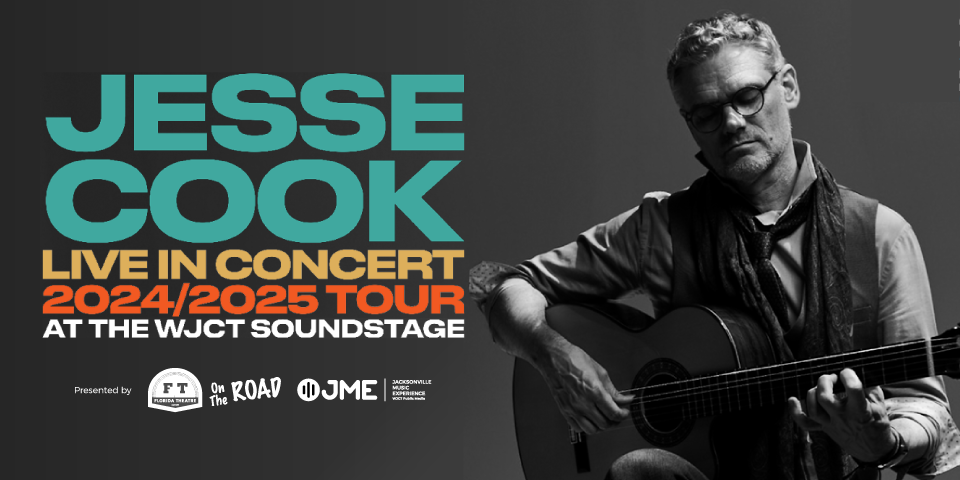

JME Live Music Calendar

Want more live music? We got you…