Are completists made or are they born? As we are now living in the Age of the Availability of Everything, the floodgates of archival, reissued and unreleased (or at-times much-bootlegged) music remain wider than the limited bank accounts of most music consumers. Thankfully, sifting through this stream of new-old music uncovers a few treasures. A pair of recent reissues from Domino Records highlight the early solo career of John Cale — an artist worthy of retrospective treatment.

A half century after their original release dates, The Academy in Peril (1972) and Paris 1919 (1973) are still-impressive albums and highlight Cale’s singular creative bravado that remains intact to this day. These updated versions of The Academy in Peril and Paris 1919 are available as vinyl and download versions, with the expected whistles and bells of up-priced reissues.

Soon after leaving the Velvet Underground (the band he cofounded) in 1968, in quick succession Cale released two solo albums for Columbia Records: Vintage Violence (1970) and, with minimalist-composer Terry Riley, Church of Anthrax (1971). Both Vintage and Church boast certain rewards, and were each recorded in three-day sessions, a scant amount of time to contain the ideas and many talents of Cale, a singer-songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, producer-arranger whose skill set remains multi-hyphenated.

In the early ‘70s, John Cale moved from the brick-and-pallor NYC to the uncompromising sunlight and swimming pool radiance of Los Angeles and was soon on the roster of Reprise Records, an interesting subsidiary label of Warner Brothers that included artists as disparate as Gram Parsons, Frank Zappa, The Fugs and Fleetwood Mac. In addition to signing as an artist to the label, Cale was also hired on as an A&R agent and producer for Reprise, roles that put him within arm’s reach of a cadre of musicians from pillar to post.

Released in July, 1972, The Academy in Peril remains a confounding listen yet benefits from the excesses of its age. Unlike his previous two solo albums for Columbia Records, Cale had time, resources, and even the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra for his flagship album for Reprise. The wordless opening cut “The Philosopher” features Ron Wood playing some jigsaw, toothy slide guitar over minimal percussive clack, buffeted by a swirl of orchestral brass and strings. The wandering solo piano piece “Brahms” and “3 Orchestral Pieces: Faust/The Balance/Captain Morgan’s Lament” allow Cale the chance to flex his classical training but are more curiosity than keepers. Ditto the track “Legs Larry at Television Centre,” which pairs Cale’s multi-tracked violas with stage directions delivered by Legs Larry Smith (of the UK satirical music-anarchists, the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band). The deluxe edition of The Academy in Peril includes the unreleased track, “Temper,” which is as consistent, and also redundant to, the rest of the album.

The Academy in Peril remains an odd duck of an album, pre-punk attitude masquerading in the gold-leafed concert hall, and hardly an entry point for listeners unfamiliar with the music of John Cale. Warner Brothers gave Cale a budget of $120,000 to make The Academy in Peril, a serious bet for a dark horse. More than 50 years after its release, the same listeners tempted to be persuaded by Cale’s legacy and pedigree might be lured into re-evaluating the album, which could also be heard as Cale’s spasmodic attempts at forcing orchestral pieces next to avant-garde recording studio hijinks. Regardless of that album’s critical or commercial successes, Cale mined creative gold with his follow-up release.

Originally released on February 25, 1973, the nine songs of Paris 1919 synthesized the melodic and lyrical ideas from Cale’s previous solo releases into a flawless collection. Produced by Chris Thomas, who, prior to Paris 1919, had previously worked with the Beatles and Procol Harum, the album documents a developmental moment when Cale merged his ideas with highly-sympathetic players. For the sessions, Cale’s group featured a concise but formidable band: guitarist Lowell George and drummer Richie Hayward were core to the sound of Little Feat, while bass guitarist-saxophonist Wilton Felder was both a founding member of the Jazz Crusaders and an in-house bassist for Motown Records.

Cale has always asked the best questions, more concerned with loss, grief, impermanence and identity rather than the shiny, shrink-wrapped pop topics of romance and finance.

Opening track “Child’s Christmas in Wales” threads together the sounds of doo-wop, Goffin/King soul, and church organ, supporting Cale’s lyrics that filter his romance through the wordplay of Gerard Manley Hopkins, sketching out a holiday reverie that is both sentimental and phantasmagoric: “Then wearily the footsteps worked / the hallelujah crowds / too late but wait the long-legged bait / tripped uselessly around.” Romance is weary stuff, a hindrance even, and Cale sounds more weakened than most on the album centerpiece, “The Endless Plain of Fortune.” Ostensibly an imagined journal of early 19th-century treasure seekers in South Africa, with “Fortune,” Cale digs deep into the loam of daybreak balladry, penning an observation on human’s fealty to attachment: “It’s gold that eats the heart away / and leaves the bones to dry.” George and Hayward inject some serious boogie pungency to “Macbeth” and the angular, ska-tinged wobble of “Graham Greene” is a certain predictor of the future sounds of UK new wave, while “Hanky Panky Nohow” and “Andalucia” are carried along by Cale’s personal style of baroque pop that rivals the similar heartaches of Arthur Lee & Love and the Zombies. Unlike the reissue of The Academy in Peril, the updated Paris 1919 adds an additional handful of unreleased, alternate tracks or mixes: “I Must Not Sniff Cocaine” is a 40-second audio verité of Cale apparently breaking his own oath on tape. Mildly ironic considering that very drug helped push Cale to eventually wave the white flag and achieve sobriety.

Cale had few peers who were equally talented and preternaturally cursed (or arguably blessed) to never enjoy commercial success and attention: Kevin Ayers, Van Dyke Parks, Roy Harper, and Annette Peacock are prominent peers who bore the similar mark; fittingly, they all continued to release higher-aiming and singular bodies of work. From the late sixties through mid-seventies, Cale was a collaborator or producer for similarly esoteric musicians, including Nico, the Stooges, Patti Smith, Nick Drake, the Modern Lovers and Mike Heron of the Incredible String Band’s excellent 1971 solo outing Smiling Men with Bad Reputations. From the late seventies onward, Cale has collaborated with Squeeze, Sham 69, Brian Eno, the Manic Street Preachers and also guested on Animal Collective’s 2016 album, Painting With. This past summer, Cale released his latest full length and 18th studio album, POPtical Illusion, an album that is full-tilt electronics and far afield from the somber wander of Paris 1919.

Now age 82, John Cale arrived in the rock and roll spotlight after Bob Dylan and the Beatles, musicians who were expected to not only entertain but guide, comfort and offer answers to their millions of adoring fans. Cale’s music has never provided answers. If anything, the music of Cale only deepens the mystery, at times operating as low-grade anthems for those existing on tenterhooks. But Cale has always asked the best questions, more concerned with loss, grief, impermanence and identity rather than the shiny, shrink-wrapped pop topics of romance and finance. Longtime fans and the curious alike can now enjoy these fleshed-out versions of ‘70s-era Cale, when his powers of blunt inquiry were both cutting and sweet.

The Academy in Peril and Paris 1919 are now both streaming on all platforms and available where all fine albums are sold.

Mr. Al Pete and Notsucal Release Their Latest Collab, ‘G4.5’

Dinner Party, Tom Misch and More from the Neighborhood with Mr. Al Pete

An Ultra-Chill Playlist from the Latest Episode of Electro Lounge

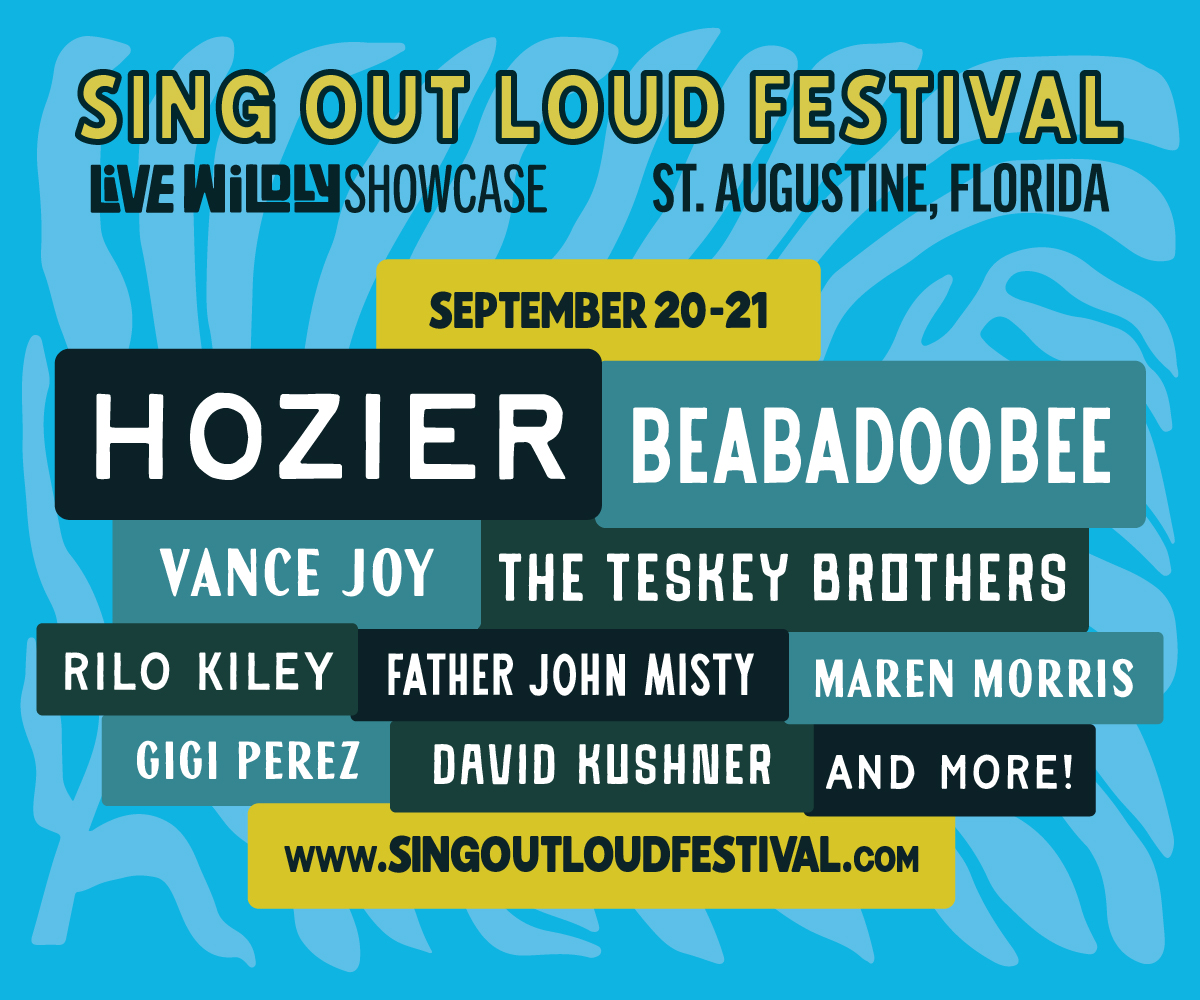

Sing Out Loud Festival Returns With Hozier, Beabadoobee, Father John Misty, Vance Joy and More

Chicago Alt-Country Faves Wilco Return to St. Augustine with Indie-Folk Great Waxahatchee

Looking for an Alternative to Spotify? Consider Hopping on the band(camp) Wagon

Khruangbin to Bring ‘A LA SALA’ Tour to St. Augustine in April

Perfume Genius, Flipturn, Tamino + Mitski and 6 New Songs to Stream

Song of the Day | “all tied up” by Glixen