Thirty-five years ago, with the release of their debut album 3 Feet High and Rising, De La Soul became a global sensation. With their flower-printed garb, rhymes that refused to adhere to standard time signatures and warbly beats as likely to be culled from samples of obscure jazz as they were classic rock, the Amityville, Long Island trio of Kelvin “Posdnuos” Mercer, Vincent “Maseo” Mason and David “Trugoy the Dove” Jolicoeur (who later went by Dave), cut unique figures in hip hop.

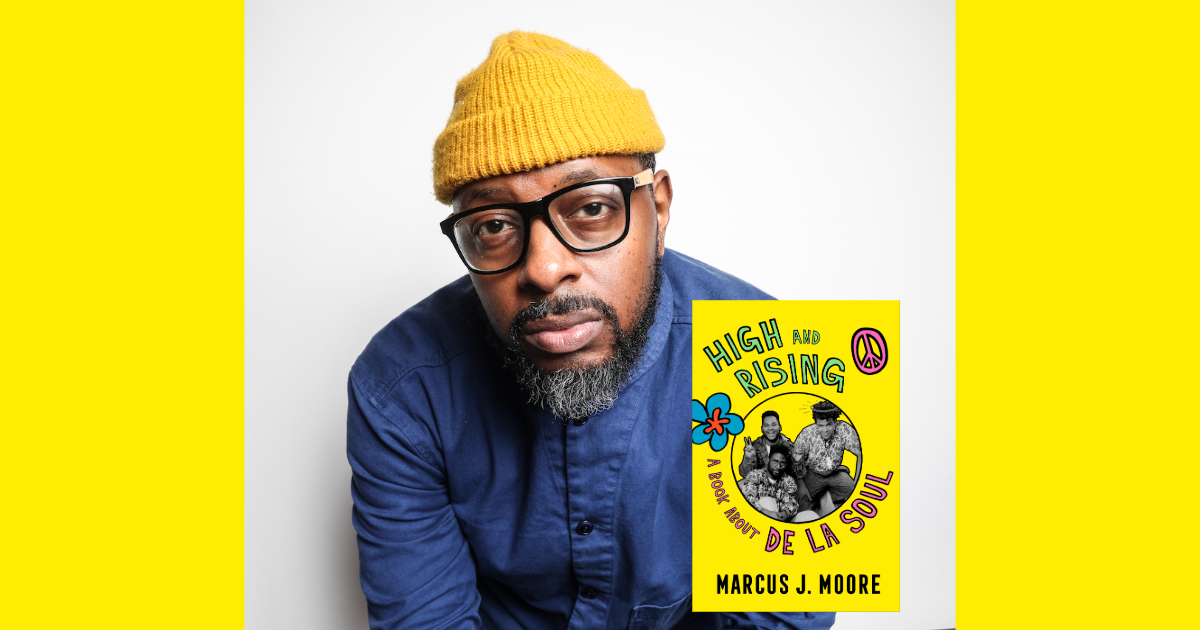

“They didn’t portray themselves as gangsters like N.W.A. or smooth-talking ladies’ men like Big Daddy Kane or LL Cool J,” writes Marcus J. Moore in his new book, High and Rising: A Book About De La Soul. “Instead, De La appealed to the Black alternative, to those who liked rap but also liked jazz and punk and maybe owned a skateboard or played an instrument in the school band.”

High and Rising tracks De La Soul’s career across three decades and makes a case for the group as pioneers, whose innovative sampling and idiosyncratic style both directly and indirectly influenced a range of artists, carving out a path for an even wider array of artists, from The Roots to J Dilla and Mad Lib, to Kanye West and Kendrick Lamar.

Though De La Soul might have hit their commercial peak with 1989’s 3 Feet High and Rising, over the next three decades the band became something of a lodestar for underground and alternative hip hop. As they continued to experiment sonically and introduced audiences to artists like Common and Mos Def, their influence on mainstream music grew more pronounced, even if that influence was not often acknowledged. Meanwhile, as the music industry transitioned into the digital era, a legal battle with their record label Tommy Boy, kept De La Soul’s early catalog off streaming platforms, a situation which lent the trio an aura of mystique, and arguably enhanced demand for their music. When the group’s Tommy Boy catalog – including 3 Feet High and Rising and the remarkable 1996 album Stakes is High – finally hit streamers in March of 2023, the celebration was muted, as the release came just weeks after the death of founding member Jolicoeur, at just 54.

Given their expansive legacy, a comprehensive history of the group – one that properly contextualizes and canonizes their music – is long overdue.

Part cultural biography, part memoir High and Rising also tracks how the group influenced the book’s writer. As an author, event curator, and music journalist whose work has appeared in Pitchfork, GQ, and NPR, among many other publications, Moore has made a career out of championing left-of-the-dial music and previously marginalized musicians. For the New York Times, he curates the popular, jazz-focused “5 Minutes to Make You Love” series.

I recently spoke with Moore about his book and the enduring, ever-expanding legacy of De La Soul. Listen to the interview via the player above or read an edited transcript below.

Marcus J. Moore. Thanks so much for speaking with me.

Hey, thanks for having me. I appreciate you.

I want to start near the beginning. You provide so much context in the book that reframes De La Soul. The group debuted in 1989 with 3 Feet High and Rising. And I think a lot of folks, myself included who maybe weren’t around then or too young, still think of them as kind of the forebears to underground hip hop. But that album was a global commercial smash. How big was De La Soul at that moment?

They were massive because this was at a time in hip hop where if you dared to be different, that meant you were gonna stand out more. So when De La Soul came out in 1989 they were so different from what everybody else was doing. If you if you think about somebody like an LL, Cool J or a Rakim, the trope for the rapper was that they were hyper masculine. They had on the Kangol [hat] with the big gold chains. It was battle ready. And De La Soul dared to be different in the sense that they were letting people know that it was okay to love, it was okay to shout people out, it was okay to be “psychedelic.” They were also pulling these sort of faraway samples. The [3 Feet High and Rising] album cover was like this day glow shade with like these pastel flowers. They were huge. But people were trying to figure out what they were. It led to people being intrigued by the group.

They were so young when 3 Feet High came out. Who were these guys? And what made them unique in the world of hip hop at that time?

De La Soul was made up of POS, Maceo and Trugoy, the Dove who later just went by Dave. They were three guys who had ties to New York City, but were living on Long Island — Amityville, Long Island. They were just regular teenagers. I can’t overstate this enough: The thing that made De La stand out was, honestly, they were just high school students who had a penchant for sort of left-of-center fashion. Maybe they loved jazz music and also had skateboards. They didn’t play into the trope that Black people were placed into by mainstream media. They were a group that showed other rappers that it was cool to have sort of a middle-class existence and to like other forms of music. As memory serves, they were one of the first groups to sample white groups. They were one of the first to sample Steely Dan and Hall and Oates. At the same time, they were these people who were just trying to dig for these far away samples. They weren’t trying to do what everybody else was doing. They didn’t limit themselves to just the box of hip hop, right? Hip Hop was great. And that’s a well enough existence, but they wanted to be in the same vein as like a Stevie Wonder or a Sly and the Family Stone, or, more directly, Parliament Funkadelic. I feel like they came from that esthetic, and that’s what sort of ushered them through their entire career.

In the book, you outline how De La Soul was quite innovative in both what they chose to sample and the ways in which they sampled. You also write a lot about how the members of the group cut unique figures in hip hop. Can you talk about the ways in which De La Soul’s influence endures in hip hop and popular music?

De La Soul made it cool to be “weird.” Before them, if you if you think about the beats, they were all very stilted. They all stayed on the grid, and they were all perfectly crafted instrumentals. When De La came along, they were pulling from like different time signatures, and and they were rapping at different time signatures. And so it created this sort of oscillating effect, almost like a free jazz, or a spiritual jazz kind of situation where you have the beat that’s doing one thing, and you have the rap that’s either fitting within the pocket or it’s going sort of counterclockwise to what the beat was doing. It scrambled your head in a really cool way. I feel like if you want to assess their legacy, you also have to consider what The Roots did in the ’90s. And what J Dilla did. Common, Mos Def, who’s now Yasiin Bey, acts like that. Their music was slightly off the grid, you know. That all goes back to De La. And it also goes back to the Jungle Brothers. I want to give proper reverence. So it’s the Jungle Brothers, De La, [A] Tribe [Called Quest], that whole Native Tongues collective. Those acts put a human element into the music. They left it open enough for human error, where you’re going to hear some static from the vocal, from the vinyl sample. You’re going to hear maybe a vinyl pop, and they’re just going to keep it in there. I would argue that without De La Soul, you don’t have The Roots, you don’t have a Kanye West, you don’t have Mos Def. You don’t have Mad Lib. Because all of these people, for lack of a better term, keep the dirt in the music. And that’s what De La brought.

You’ve spent a lot of your career, and are now known widely for, championing left-of-the-dial music and marginalized artists, not just in hip hop but maybe even more prominently in jazz. Can you talk about the ways in which De La Soul’s music sparked your curiosity and put you on the path to doing the things you do today?

By the time De La Soul came out, I was a child, but I was already deeply embedded in my music curiosity because I was an MTV kid. So I remember when MTV started, and I’m in front of the TV looking at Madonna, The Cure, Duran Duran, Michael Jackson. I’m looking at all these different artists at the same time. I was just fascinated by it. And it was the same thing with De La. I’d been listening to Public Enemy, Boogie Down Productions, NWA, MC Lyte. And then when De La came along, I remember when I heard “Plug Tunin’.” It sounded like the beat wasn’t even finished, or like it was made on a cassette and it wasn’t mixed or mastered. It just had this muddy sound that just hit my ears in the right way. Everything else of that era might have been a little up tempo. We were all dancing hard back then. I remember “Potholes” because it almost sort of stumbled out of the speakers in a way. There’s yodeling on it. I’m thinking, “What is this? I don’t know what’s going on on this song, but I just need to know more.”

“They were a group that showed other rappers that it was cool to have sort of a middle-class existence and to like other forms of music.”

-Marcus J. Moore on De La Soul

So I say all that to say that I was already a naturally curious person musically. And De La provided homework in a way. To the point now, to your question, when I’m covering jazz music, when I’m covering experimental music, I’m always looking for the intention behind the music. My ear bends towards music that has a little bit of dirt in it. If you think about 3 Feet High and Rising, nothing is really perfect about that album. But it works in a way because it just feels like your older brother or your older cousin talking to you. And the conversation is not always going to be linear. It’s going to go down this valley and that valley. And I feel like throughout their career, they were the masters of that.

Lastly, as the music industry transitioned from physical formats to digital and then streaming, much of De La’s early catalog was unavailable on music-streaming platforms. As you describe in the book, those were lean years for the band, financially. But how much do you think the inaccessability of their music during that period contributed to the group’s popularity?

That’s a great question, because I feel like that’s a part of marketing that’s really talked about enough: the mystery. Even if you look at mainstream artists now, like Kendrick Lamar is a master of mystery. You’re not going to hear from him until he’s coming out with a record. Or somebody like a Sade. We all clamor for a Sade album because she hasn’t said anything in years. We haven’t heard from her. So it’s the same with De La. Their music definitely has a you had to be there element to it. Yes, the narrative around De La’s lack of streaming and their publicized struggles with Tommy Boy Records played well into their coming back. The fact that you know you couldn’t just hop on Apple Music and play Stakes is High, I think lent to the popularity of the group. It kind of threw back to the old mixtape culture, or dubbed cassette culture, where if you didn’t have the tape, somebody would dub it for you and pass it along. And that’s what we were doing with De La’s music for the past 20 years — you were whispering to somebody, “Hey, do you have a copy of De La Soul’s Dead? Send me the Mp3’s. But I also feel that De La has this incredible fan base where we all uphold them because we all remember what it felt like when the music came out in the ’80s. Unfortunately, we’ve lost Dave. But those guys are just really nice guys that people love. So people want to jump up and protect them, no matter the music that’s coming out, no matter when it comes out. So there’s two things factoring in there: It’s the mystery, but also the fact that they’re just really good dudes that people want to see win.

Well the book is High and Rising: A Book About De La Soul. Marcus J. Moore congrats on the book and thanks so much for speaking with me.

Thank you. I appreciate you.

High and Rising: A Book About De La Soul Book is out now on Harper Collins. Links to order here.

New Flying Lotus, Yussef Dayes & Tom Misch, Plus Black Violin and Local Music from Dylan & Batsauce on The Neighborhood

Jacksonville-Based Bonnethead Deliver Shoegaze Goodness on “Dive”

New Music from Tinsley Ellis, Keb’ Mo’ & Heavy Doses of John Mayall, Stevie Ray Vaughan from Blues Horizon

The Foreign Exchange, Stro Elliot, Tall Black Guy, Lupe Fiasco and More New Music from the Neighborhood

The Loving Arms Race Roll Away the Stone with their Rollicking Debut Release

Sunny War Returns to Jacksonville to Play Intuition in November

Kale That Raps Drops New Album ‘It’s Personal’ Ahead of Porchfest Set

UK Shoegazers Slowdive to Kick Off New Fall Tour at St. Augustine Amphitheatre

Song of the Day | “NOID” by Tyler, The Creator

Ann Powers and Alison Fensterstock on ‘How Women Made Music’

JME Live Music Calendar