In the 2021 HBO documentary Jagged, which looks back at the making of and reception to Alanis Morissette’s album Jagged Little Pill, a DJ from the Southern California commercial radio station KROQ recounts how, when Morissette’s song “You Oughta Know” was barnstorming the charts, the station had a policy of never playing songs by women artists back-to-back.

That was the summer of 1995. Jagged Little Pill now stands as the second-best-selling album of the ’90s, despite the glass ceiling that limited its airplay on mainstream radio. As the DJ in the documentary says: “That’s just how it was.”

But that’s not only “just how it was” in the world of commercial radio. A similar inequity has long permeated the ways in which music is disseminated and discussed. From the shelves of your local bookstore to the pages of the once-robust industry of print magazines, men in music are more often exalted than women.

For example: There’s the seemingly insatiable appetite for books about the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Bruce Springsteen. The household names of music writing – see: “The Dean of rock criticism” Robert Christgau or the “Poet Laureate of punk” Lester Bangs – are men. The amount of books about Bob Dylan written by Greil Marcus, alone, outpaces the scholarship dedicated to Joni Mitchell. Infamously, last year when Rolling Stone Magazine and Rock ‘N’ Roll Hall of Fame founder Jann Wenner released his book of interviews with the “masters” of rock, he neglected to include a single female artist. (Wenner was removed from the board of the Rock Hall after telling the New York Times that, in regards to the exclusion of women from his book, “Just none of them were as articulate enough on this intellectual level.”)

It’s that kind of marginalization of women in the historical narrative that critic Ann Powers has been trying to remedy since she began writing about music. The same year that radio stations were barring their DJs from playing songs by Alanis Morissette before or after songs by, say, Bjork or PJ Harvey or No Doubt – all of whom released groundbreaking albums in 1995 – Powers co-edited a book called Rock She Wrote, the first-ever collection of music writing done entirely by women. Since then, as an author of music books (including one about Joni Mitchell), a pop critic for publications like the Village Voice, the Los Angeles Times and NPR Music, as well as one of the most well-respected and widely read music writers of her era, she’s done much to reshape the narrative around women in music.

In 2017, Powers co-founded the NPR Music series Turning the Tables. The series started with a list: The 150 Greatest Albums Made by Women. A famously list-centric beat, music journalism’s glut of “greatest” and “best” lists left Powers and Turning the Tables editor, the New Orleans-based writer and radio host Alison Fensterstock, with many questions. “Why are some of our favorite artists not considered the greatest,” Powers said when I interviewed her and Fensterstock. “And why is it that even the biggest names like Aretha Franklin or Joni Mitchell are never number one?” Through podcasts, live performances, videos and essays by an all-star cast of women writers – from the novelist Dawnie Walton writing about Santigold, to the scholar Francesca T. Royster on Tracy Chapman, to music journalist Lindsay Zoladz on Fiona Apple, among many others – the series centers women in the history of popular music.

A new book How Women Made Music: A Revolutionary History from NPR Music, edited by Fensterstock with an introduction by Powers, builds on the work of Turning the Tables. In addition to essays culled from the series, the book draws on more than 50 years of NPR’s coverage. With its range of voices, not only is How Women Made Music arguably one of the best collections of music writing in recent memory. The book also – through historical interviews from the NPR archives – makes space for iconic artists like Patti Smith, Dolly Parton and Nina Simone to talk about their craft, careers and the music that inspired them, creating a framework for women to be seen and heard as more than musicians but, as Fensterstock said, “a person with their headphones on, listening to a record, or a person scribbling in their diary,” or “as creators, as listeners, as critics,” and “appreciators” of music.

I recently spoke with Powers and Fensterstock about How Women Made Music. You can listen to an audio version of that interview above or read an edited transcript below.

Alison Fensterstock and Ann powers. Thanks so much for speaking with me. I’m excited to talk to you about this book. It looks like a massive and important undertaking.

Alison Fensterstock: Well, thank you. It’s great to be here.

Ann Powers: Yeah, thanks so much for having us.

So the book is How Women Made Music. And it’s drawn in large part from the series Turning the Tables, as well as the NPR archives. You’ve both contributed to Turning the Tables, and it’s grown to be kind of this multimedia environment with podcasts and live performances and video. Can you talk about the framing of the series and the impetus behind starting it?

AP: Well, quite a long time ago now, Alison and I were with our friend Jill Sternheimer in New Orleans at a show. It was this amazing guitarist named Barbara Lynn, and she’s great. She was a pioneer. She’s, I don’t know, Alison, how old is she now? In her eighties or something?

AF: Gotta be in her eighties. Yeah, left-handed guitarist from Beaumont, Texas.

AP: We were talking about how we never hear her mentioned in lists of great guitar players. And why is that? And then that led to a bigger conversation. Why are some of our favorite artists, even if they are acknowledged, like say, Rickie Lee Jones, while she might be acknowledged by a lot of people, she isn’t always on the lists of the greatest. And then why is it that even the biggest names like Aretha Franklin or Joni Mitchell, they’re never number one. They might be number eight or something like that on all these lists. So we thought, how can we fight back against this obvious sort of marginalization of women? And the solution we came up with initially was, what if we told the history of popular music only through the voices and stories of women? So the first thing we did was make a list of the 150 Greatest Albums by Women. And from then on, it just grew and changed. And finally, we came to a point where we felt we should compile all this into a book. And we also got the idea to expand it by including interviews with artists or excerpts from interviews with artists from throughout NPR history. And now we have this fabulous book.

The essays that have been contributed [to Turning the Tables] are by women journalists and women writers who maybe aren’t music journalists. It’s really an all-star cast. I was excited to see — and I think I learned this through social media — Elizabeth Nelson [included], who’s writing I adore. And the jazz-radio-host, podcaster, tastemaker Keanna Faircloth. Some really fantastic writers. Can you talk about the collection of voices that you curated for the series and then included in the book, and maybe what you hope readers will infer about the state of music writing?

AS: Oh, that wound up in an interesting place.

AP: We love these questions.

AF: The initial collection that started the whole thing, the list of 150 Greatest Albums by Women, was made with a lot of people that were working in music journalism and also NPR hosts that weren’t necessarily covering music, but were very excited to jump in. And then, as the series went on, we were able to invite people like fiction writers and some other writers that just had really interesting personal-essay perspectives and memoiristic reads on the music that they were listening to. And then we found, for the book, Elizabeth Nelson. We got her specifically for the book. I had made friends with her on Twitter, and I’m just obsessed with her, like incredibly concise and efficient descriptions of albums. She’s an amazing writer, and I’m so glad to have her in here. And we also have some scholars, like Melissa A. Weber, who’s the curator at the Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University in New Orleans, where I live. I knew she was a big Parliament Funkadelic head. She was obsessed, especially with the Brides of Funkenstein and the other women that were part of the whole collective. So we let her loose to write an essay defending them. And we also have musicians like Kaia Kater, who wrote a great piece on Rhiannon Giddens and her influence on her as a musician and as just a thinker, and someone who was conscious of the history of the music she was playing. So we have perspectives from across the board.

AP: One of the beautiful things about music writing right now, even as you well know, I’m sure Matt, the media seems to be shrinking, the outlets seem to be falling one by one, and we can kind of get in a dark place, if we think about that. But music writing has actually grown in these incredible ways over the past few decades. As Alison mentioned, scholarship. Writing within academia about music has just totally blossomed. And so many women, especially women of color, are doing great work in the field of music scholarship. And we have many of them in this volume, from Farah Jasmine Griffin to Karen Thompson to Maureen Mann. When I started as a music journalist, back in the prehistory, the age of the dinosaurs, I was often the only woman in the room. I was often the only woman or one of two or three on a given masthead. And now so many of the top jobs belong to women, whether editorial jobs or columnists. And we’re really happy to have many of those women in this book, and they’ve contributed to the series over the years. So did we help form that community. I like to think that we did, actually, I’ll give myself, I’ll give ourselves a little credit for that. At the same time, it’s just been a thrill to be part of the sea change.

You’ve both been in the music journalism game for some time now. I want to go back to when you were starting out. I know that, at least into the ‘90s, there was an unspoken rule in radio, something like you can’t play to female-led acts back to back. Music media, print media specifically, was much more robust than it is today. What it was like writing about music when you started. Were there parallel rules in place?

AF: I don’t know about rules. I started a little bit later than Ann and I worked at a daily newspaper in New Orleans and an alt weekly. So I covered a lot of local music. But also at a daily paper you have to be a generalist. And I think I chose to cover women artists more often than not because I didn’t think anyone else was going to do it, which may be an experience Ann had as well. You sort of accidentally wind up putting yourself into that box, because, like, no one else is going to cover the women. So then you become the woman-woman [laughs].

AP: The woman-woman! Yeah, that definitely happened to me. And I will say one thing about this book that feels very full circle to me. Back in the mid-’90s, my friend and colleague Evelyn McDonnell and I edited a book called Rock She Wrote, which was a collection of women writing about popular music. It was the first collection ever of all women writing across genres about popular music. And we had this amazing time doing that, not only bringing the world around to these women writers, but in some ways, introducing them to each other across generations. And I am very proud that we now have another book that celebrates the newest generation of music writers as well as some elders. I mean, the age range of writers in this book is quite great, from women in their twenties to women at least in their sixties, maybe even older. And so I just want people to know that women have been writing about music for as long or longer than men. I did some research once into the very early days of rock ‘n’ roll. And you know, what’s interesting: The first writing about rock ‘n’ roll was really by women, because it was considered a youth phenomenon. It was women reporters who were going to those shows, going to the Alan Freed-sponsored shows, going to early Elvis shows, writing about phenomena like Beatlemania in what was then called the Women’s pages. Same in the Black press. That same thing was happening.

The book also features artists talking about their work, their creative process, what it means to be an artist. Joan Baez talks about nonviolence. Dolly Parton on her favorite song. Nina Simone, Odetta, Taylor Swift. What will folks find interesting about the discussion of the creative process and why was it also important to make that a pillar of this book’s contents?

AF: Well, I think one of my favorite parts of the book is when I went into those NPR archives and found the quotes from the artists in their own voices being interviewed by NPR at some point in its 50 year history, talking about their process, talking about their work as an artist, going behind the scenes. But there are also a few in there that I love, because it’s artists talking about the influence of other artists on them, or what they’re seeing as a listener. There’s a quote from, I think it’s in 2007, Queen Latifah talking about how impressed she was by Lauryn Hill when she came out. Or there’s a great interview with Carole King. I think she was on Fresh Air, saying it just blew her mind to hear Aretha Franklin singing her song, “Natural Woman.” So you get this interplay where, even an artist, even a composer, is still a person with their headphones on, listening to a record, or a person scribbling in their diary. I think that’s a really important thing about the way the book is put together. It’s not just these biographies of people and the work they made. It’s sort of the way they interact with music in this 360-degree way, as creators, as listeners, as critics, as appreciators.

Ann Powers and Alison Fensterstock, thanks so much for your time.

AF: Thank you.

AP: Yeah, thank you so much.

How Women Made Music: A Revolutionary History from NPR Music is out now. Learn more and purchase a copy here.

Mr. Al Pete and Notsucal Release Their Latest Collab, ‘G4.5’

Dinner Party, Tom Misch and More from the Neighborhood with Mr. Al Pete

An Ultra-Chill Playlist from the Latest Episode of Electro Lounge

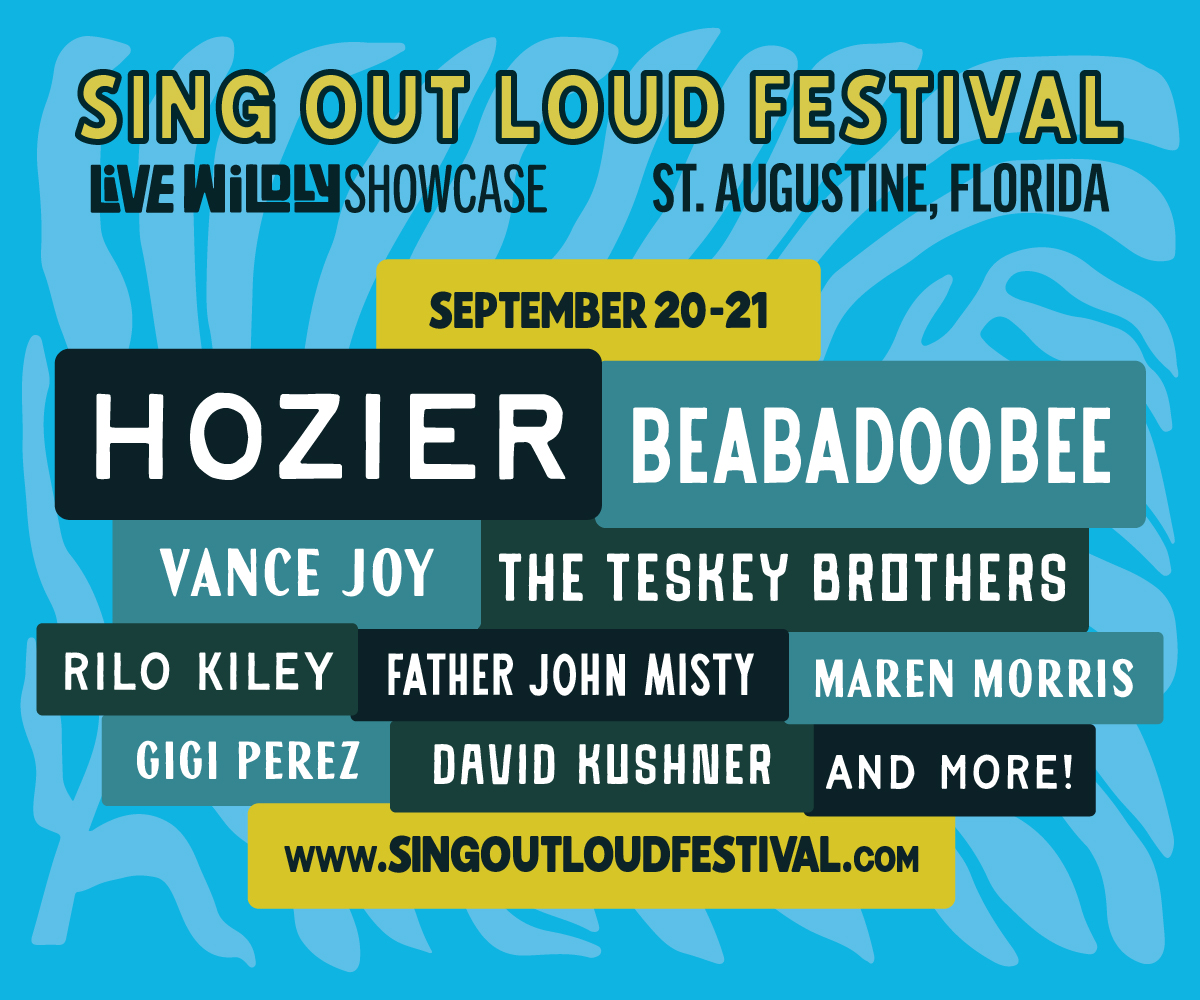

Sing Out Loud Festival Returns With Hozier, Beabadoobee, Father John Misty, Vance Joy and More

Chicago Alt-Country Faves Wilco Return to St. Augustine with Indie-Folk Great Waxahatchee

Looking for an Alternative to Spotify? Consider Hopping on the band(camp) Wagon

Khruangbin to Bring ‘A LA SALA’ Tour to St. Augustine in April

Perfume Genius, Flipturn, Tamino + Mitski and 6 New Songs to Stream

Song of the Day | “all tied up” by Glixen