Judging by the early-21st-century proliferation of the memoir, there is a deficiency of connectedness in this world. Social media is a certain culprit, with its fertile platforms that allow us to offer curated life-narratives while internally some are dying on the vine. Combined with the proliferation of wellness podcasts and attendant merchandising, the early 21st-century is apparently a place to feel both disconnected from humanity and appropriately unwell.

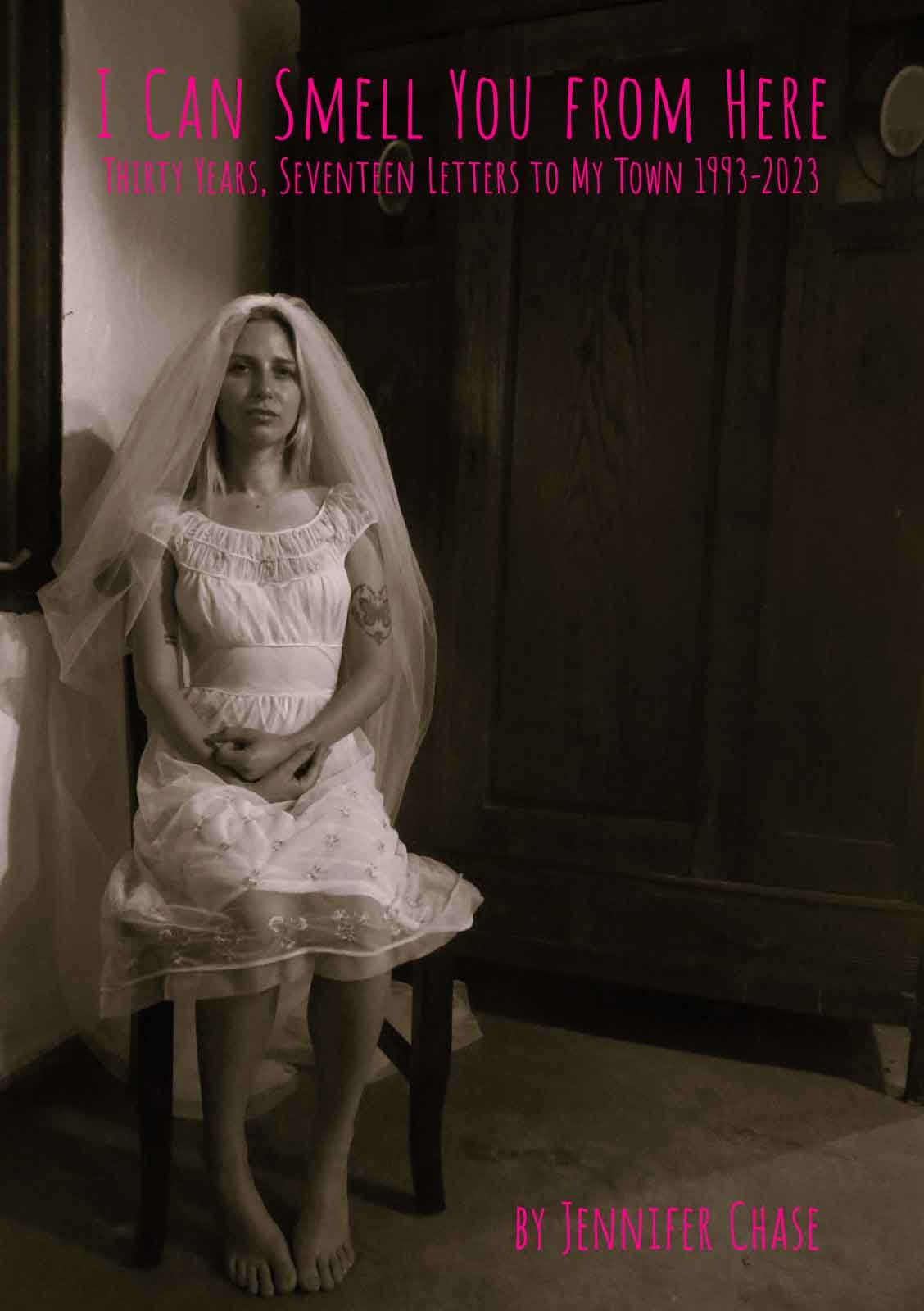

Locally, Jennifer Chase has just published a fairly fearless memoir: I Can Smell You from Here: Thirty Years, Seventeen Letters to My Town 1993-2023. While hardly a tonic for society’s ills, I Can Smell You from Here is a well-written, image-rich travelogue through Chase’s artistic and personal life as she figures it out, in real time.

Over the course of the 366 pages of I Can Smell You from Here, the city of Jacksonville is a looming, permeating character. There are also cameo appearances by international cities where Chase sought her fortune and created art. The book is also celebration of an invisible legacy of the highbrow monied arts movers and low-key pool-hall players who move through Chase’s life: some arrivals in her book boast VIP-status but the oddballs and allies Chase has attracted are mostly somehow countercultural in their inclinations.

Chase is expert in her rhythmic flow of words. A volley of information and scenery is sketched out into paragraphs, then shifts gears with one staccato sentence that redirects the story flow. I Can Smell You from Here is candid, a crucial historical document of a specific milieu and epoch of the Jacksonville arts galaxy and also highly readable. Passages of the book run from the poignant and hilarious to the discomforting. Chase writes at the level of rigorous authenticity and doing the uncomfortable work, doubling down on what she has experienced, her assets and flaws, dreams fulfilled and dreams that fell flat.

“What began as a presumptuous confrontation of Jacksonville for its lameness, turned into a revelation of some of my own lameness and a much more complex relationship with Jax where I had space to fail with a mixture of extraordinary characters in the music scene who shaped my experience.”

A decades-long presence on the Northeast Florida creative community, Chase has previously released five albums of music, created a one-woman show, and penned theatrical dramas, including Handmaid, as well as the musical Majigeen and collaborated with John E. Citrone on a rock opera, La Caroline. In addition to this body of work, Chase is a tenured creative writing professor at Florida State College of Jacksonville and also founded and produced the music-activism venture J.A.N.E. (Jacksonville Artists’ Night of Entertainment), a musical platform where women performed original music to raise awareness and money to address the high cost of childcare.

Considering her peripatetic, idiosyncratic life arc, it’s no surprise that Chase is also a musician and singer-songwriter. Her previous music includes the albums kid jail (1994); famadihana (1998), the single “Anta Majigeen Njaay” (1998) which Chase wrote and recorded in Senegal with guest vocalists, and accompanying album for her stage production Artichoke Soup (2012), released under Chase’s alias: Jacinta Chaminade.

In conjunction with the book’s release, Chase also produced a new EP of original music that shares the same title as her memoir. Produced with longtime Jacksonville bassist-producer Roy Peak’s studio, Chase is joined by Darren Ronan (drums), Holly Decardenas (cello), Michelle Bajalia (keyboards) and Lauren Fincham (vocals). The seven songs of the EP are akin to the tender-leaning songs of Lucinda Williams in a style that could be described as saloon-baroque.

This Friday, May 17, Jennifer Chase is featured in a reading and performance of her new music at Happy Medium Books in Avondale. The ticket price includes a copy of the memoir. JME offered up our takeaway and interrogation of Chase, to which she graciously agreed. What follows are highlights of email correspondence.

The title of the book is pretty humorous and surely intriguing. Could you explain how the title came to be?

Yeah. I’m a smell person. People close to me know that. I smell stuff and people I love, their 25-year-old pajamas, rooms, wood, moments, etc. There are many people I don’t smell. I mean way more people I don’t or won’t smell. It’s a pretty intimate deal. The smell can transport me back in time to a feeling or a place. You know how a song can do that sometimes? Jacksonville definitely had a distinct smell the first time I came here (in 1983 for a Stevie Nicks concert). It was not good. I told myself I could never live in a place that smelled like that (in the book I describe it as burnt corn husks and melted plastic, which is accurate.) In the book I use smells as “scent prompts” that introduce each letter to Jax. During the writing process and it took me back to that particular moment that I’m writing about for better or for worse. I wish I could have had a scratch and smell book. Do you remember those? I actually tried to do it, but no one wanted to deal with me. I settled on bottling some of the smells and I pass them around during my readings.

You chose to write I Can Smell You From Here as an epistolary. What compelled you to use that particular literary form?

Yeah, I’m writing letters to Jacksonville. Second person is underrated. It can be an effective creative device for the writer and the reader. The “you” in the story or song enhances one’s ability to imagine another perspective, to be empathetic. “You” gotta be careful though, because it also can be judgmental and preachy. What began as a presumptuous confrontation of Jacksonville for its lameness, turned into a revelation of some of my own lameness and a much more complex relationship with Jax where I had space to fail with a mixture of extraordinary characters in the music scene who shaped my experience. [The memoir] began as a meta letter—cathartic. I had to discipline myself to keep going back and make sure that I was really being honest with Jacksonville and not inserting exposition, things I wouldn’t really say, just to inform the reader.

In a message to me, you explained that, “This memoir almost killed me to write. The musical collaboration saved my a**.” What were some of the hardest aspects of writing this memoir; did those elements in some way alter your original motivations to even write the book?

That’s funny that I said that. It sounds so “Joan of Arc-y,” like the demand was so high for my story and I sacrificed myself to get it to the clamoring masses. I applied for an Art Ventures grant from the Community Foundation for Northeast Florida. I proposed this project. It was sort of a dare to myself that if I got the grant, I’d have to do it. I wanted to find meaning, engage new audiences in my work— a thirty-year body artistic work—in new ways that followed cohesive threads. I knew I didn’t want an anthology of sh*t. I wanted stories about the stories of the songs, people, plays, and all the drama and failures interwoven in my life here. When I got it, I was terrified. What if I don’t have anything new? I wasn’t comfortable in my new age or skin. We are harder on women. Recent years I’d focused primarily on self-producing my plays and trying to get them professionally produced. I had gotten away from music and hadn’t written a song in twelve years. Reflecting on the songwriting process and the people that I met here and loved in the music community was like an exhale. I started inviting people over to my kitchen that I met back then who were doing cool things in the music scene here: Mike Shackelford, Dave Roberts, Andy King and Lauren Fincham. I created a chain visually of who introduced me to whom. It was like I stripped down the bullsh*t and remembered who I really am. It’s unpretentious. There’s a presence, an understanding, an acceptance. I was immediately happy. I’m a messy and obsessive writer. I don’t give up. But my process goes on for months of writing before I even understand what it is I’m writing. I wish I could be super economical churning stuff out, but I can’t. I have to follow my intuition and research, go down rabbit holes, cry, lament, get pissed at myself and smell the stories that come up. It’s painful. But at least it’s real. I know what is real and what is gratuitous.

How does the music EP tie in to the book? Are the songs commentaries on moments in the memoir or are they standalone musical pieces?

Yeah. Everything, the smells, photos, the EP, as well as songs from all my five original albums, ties in. Each letter to Jax is chronological and focuses on an artistic project or an artist I met and a resulting song from that period or some aspect of it. My book layout designer (who’s a very cool, dyslexic Italian woman living in New Zealand) had this kind of brilliant idea to add QR codes to the selected lyrics at the end of each letter. I love that readers can interact with the music if they want to from 1993-2023. The EP features the merciful break in the 12-year songwriting block, the song “Houston and Lee” that revealed itself very late in the process.

Could you describe your actual writing process and the development of this book. Did it initially start as an essay or memory exercise and evolve or did you set it to write a memoir? How long did it take to complete the final manuscript?

I’m a morning writer. I wish I were at a party in Istanbul, cigarettes-and-gin-at-a-typewriter writer like Baldwin, but my creative clock is best sober and at 4 a.m., from my bed directly to my treehouse. The timeframe alone of [the memoir] breaks all of my own rules of what I think makes a good memoir. The best memoirs are disciplined and crystalize a brief period of time. Just Kids by Patti Smith is a great example of this. She focuses on a particular period of time from around age 17 to early 20s and predominantly focuses on one relationship. She doesn’t try to work everything in from her whole life. I knew that if I was going to focus on my thirty-year period as becoming and creating as an artist in Jax, then I would have to adhere to rigid parameters regarding my theme, focus and concept to make it good. I also knew that I’d need at least as much time to edit/revise and cut as I needed for the initial writing. I’m a macro-to-micro person and make a huge mess. The Art Ventures grant period was initially supposed to run Spring of 2022-2023. By June 2023 (the end of the grant cycle), I hadn’t spent any of the money yet because I wasn’t ready to bring anyone else in yet. I wrote to the Community Foundation to offer to give them the grant money back as, after writing for months it had only just begun to reveal itself for what it was supposed to be. They said that many artists need more than a year and gave me a six-month extension. I went to my mother-in-law’s [home in] Spain for the summer and wrote in the libraries of the museums every day for hours. It was surreal to be in dark and frolicking periods of my past in that setting. Who wants to wallow in the past when you’re in Madrid in the summer? Me. I have no medium setting and I knew it would get much worse before it got better. I continued back at home, and recorded at Roy’s. It was a great productive time. I finished at the end of October.

While you’re mostly magnanimous throughout the book, you also wrote about many people and peers who are still alive and who are also active in the local arts community. Was the reality of trying to write candidly about these people in spite of potentially hurting their feelings or embarrassing them an impasse in the actual writing process?

Well, I’m trying to go through the list of people in the book in my mind and remember to whom you may be referring. There is some legitimate darkness. “Letter 7” in the book is about a very dark period. It was important to include it, but not all details. It’s its own story for another time. It’s serious and painful. In other instances, I chose to put an asterisk whenever there was a side story that was unpleasant or where I may veer off the topic, or have had a strong urge to air the person’s bad behavior, betrayal, or committing the unforgivable crime of not caring about me as much as I think they should have. I also probably have a subjective view of my experience. In short, I hold grudges. I wish I were more mature than that. If people hurt me, I want them to hurt back. Petty and sophomoric? Yes. So I tried to be, fair, honest and strict. If it didn’t belong in this story, I left it out. Once my dad wrote letters to any relative or family friend who didn’t show up at my mom’s funeral saying how sorry he was that they couldn’t make it and putting an asterisk next to his signature that he got from Kurt Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions where he uses it to represent an a**hole. None of the recipients of the letters knew that of course, but it gave my dad a little charge. I practiced uncharted realms of maturity and restraint.

There’s a great passing line in the book, where you are describing the hassles of keeping a production of Majigeen in motion: “It’s like a drug habit, only there’s no detox that I know of.” Do you think you have a compulsion to create which veers into the unhealthy?

Well, that’s a loaded question. Drug habits. Luckily the 1980s didn’t fall into the memoir’s scope of my thirty-year artistic journey in Jax. It would have been an even longer book. I was never the kind of person who could smoke bong hits, drop acid, then go study for a physics exam or write a novel. I could sit on the floor and maybe eat a burrito or something then make long distance calls to California. I think for me creating is definitely healthy. When the creative process is going right, there is nothing that comes close. Time, money, fatigue, problems…nothing matters but the present and the process. I love those magical moments. I’ve had them alone while writing in my treehouse at 4 a.m., in a rehearsal with a cast and director, or recording a song. It’s almost always during the process, not the produce. It’s not going right a lot of the time, but the memory of the feeling when it has gone right keeps you trying to create over and over. It must be like a longboard surfer who invests hours, days, weeks, months of their life paddling out and waiting for a wave compared to the relatively small amount of time they’ve spent inside a glassy tube of a perfect wave.

Throughout the book and along the journey through many of your projects, you go into blunt detail about the tedium and non-romantic hassles of creative endeavors (“The business of art is weighing down my friendships, homelife, and the relationships with my creative collaborators…It seems everywhere I turn, money wrecks everything.”) How has your relationship with money and art changed over the years?

My relationship with money hasn’t changed at all. I seriously hate it. I wish it were never invented. Time is way more important to me than money or stuff. Barter is more my style. I had to self-produce my work to get it out. That is still the case. I enjoy the challenge and the creative aspect of that, but once I transition from creator to “producer” of my plays, the dynamic of my relationships with other artists involved changes. I’m no longer a fellow artist hanging out having drinks, talking about dramatic devices and themes, tinkering with costumes and hanging with the band arranging songs. I’m the person managing the grant or stipend. It becomes a wall. My mentor from grad school reminded me one day that most people write and send, never producing their own work, let alone everyone. I’ve self-produced all of my plays. Maybe my time would have been better spent revising and sending, but the thrill of the creative process was invigorating and hearing the voices of my characters, too. I don’t regret that. It was a choice. You can wreck your own stuff by self-producing and miss professional opportunities. Rediscovering my singer-songwriter local friends freed me from that.

I remain intrigued by artists’ relationship with the “inner critic.” Barring being a total psychopath, I believe that any creative person contends with the inner voice of doubt and self-judgement. The irony being, with success comes exposure and then the audience includes actual critics to doubt and judge one’s work. How do you navigate your own doubts when you are in the process of writing—and how do you now deal with the inner critical voice?

My inner critic has evolved beyond the immediate inner voice mocking myself with endless choruses of, “You are such an idiot.” I’m getting better at identifying gratuitous and or forced lines. I’m getting stronger with cutting what don’t push the story forward (with the exception of these rambling interview answers.) I’ve actually never received critical reviews or acclaim for my artistic work here. I do not know of this success, exposure and “actual” critics of which you speak. I wish we had more of it.

Are there certain ideas or projects that you would like to see to fruition; what are you currently working on?

I’m on sabbatical from FSCJ and just finished a month-long writer’s residency at Arquetopia Foundation International Artist Residency in Cusco, Peru. I began an essay called “Chasing My Tale,” a self-confrontation about my role and responsibility as an artist and person especially in this horrific period of genocide right before our eyes in Gaza, muting freedom of speech about it on campuses, this governor’s attempts to abolish academic freedom, critical thinking and liberal arts education among myriad other worries. The residency’s director, Francisco Guevara works individually with artists and assigns scholarly readings, encourages following one’s intuition, relinquishing artistic intention and a commitment to responsibility to react. Concurrently, I began a series of ten poems and lyrical short stories there entitled, “Tendederos” (clotheslines) which examine colonialism, empire, power, race, exceptionalism, my cultural mutual encounters, friendship and trust. It was my second experience in residence with Arquetopia. There is a poem dedicated to Francisco, entitled “Ariadne’s Assassin.” My first residency was in Oaxaca, Mexico in 2023. It’s loaded with intellectual, academic, and artistic challenges. It’s hard. I’m also going back to Roy’s next week to begin recording a second EP. It feels good to engage, struggle and doubt. Then suddenly stuff spews out. Just like when I was thirty. It is present. You are part of the present. Artistically alive. When it’s there you know it. You just know. That is invigorating.

A Night with Jennifer Chase is held from 7-8:30 p.m. Friday, May 17 at Happy Medium Books in Avondale. Ticket price includes a copy of the memoir, sangria, and light hors d’oeuvres. For more info, click here. The EP I Can Smell You From Here is available on all streaming services here.

Mr. Al Pete and Notsucal Release Their Latest Collab, ‘G4.5’

Dinner Party, Tom Misch and More from the Neighborhood with Mr. Al Pete

An Ultra-Chill Playlist from the Latest Episode of Electro Lounge

Sing Out Loud Festival Returns With Hozier, Beabadoobee, Father John Misty, Vance Joy and More

Chicago Alt-Country Faves Wilco Return to St. Augustine with Indie-Folk Great Waxahatchee

Looking for an Alternative to Spotify? Consider Hopping on the band(camp) Wagon

Khruangbin to Bring ‘A LA SALA’ Tour to St. Augustine in April

Perfume Genius, Flipturn, Tamino + Mitski and 6 New Songs to Stream

Song of the Day | “all tied up” by Glixen