Thirty years ago, a friend who had played in bands in NYC in the mid-1980s told me of an interesting phenomenon. At that time, Sonic Youth were rapidly ascending from the herd of underground, post-hardcore bands.

Especially on these shores, Sonic Youth were a quixotic and enigmatic band: using alternative guitar tunings and songs that could shift from dreamlike to brutal, Sonic Youth kept one foot planted in high-art sensibility, the other slipping in the soggy bog of transgressive hardcore punk and pop cultural morass.

My friend recalled seeing Sonic Youth live in NYC, even regularly sharing bills with them at CBGBs and noticing a distinct takeaway on a night that the band (guitarist-vocalists Thurston Moore and Lee Ranaldo, bassist-vocalist Kim Gordon and drummer Steve Shelley) opened for the instrumental band Blind Idiot God, an already well-established avant-rock group. The next day, people who had attended the show remarked at how “Blind Idiot God sounded like Sonic Youth.” This same friend witnessed this same phenomenon more than once, where an audience would somehow imprint Sonic Youth on adjacent bands. That occurrence points to the band’s ability to align themselves with various other artists, scenes and trends, and somehow assimilate, translate and reconfigure it all into their own work. No fault, no foul but Blind Idiot God are mostly forgotten. Sonic Youth have ascended to a sound-as-signifier and a seal of approval and respect.

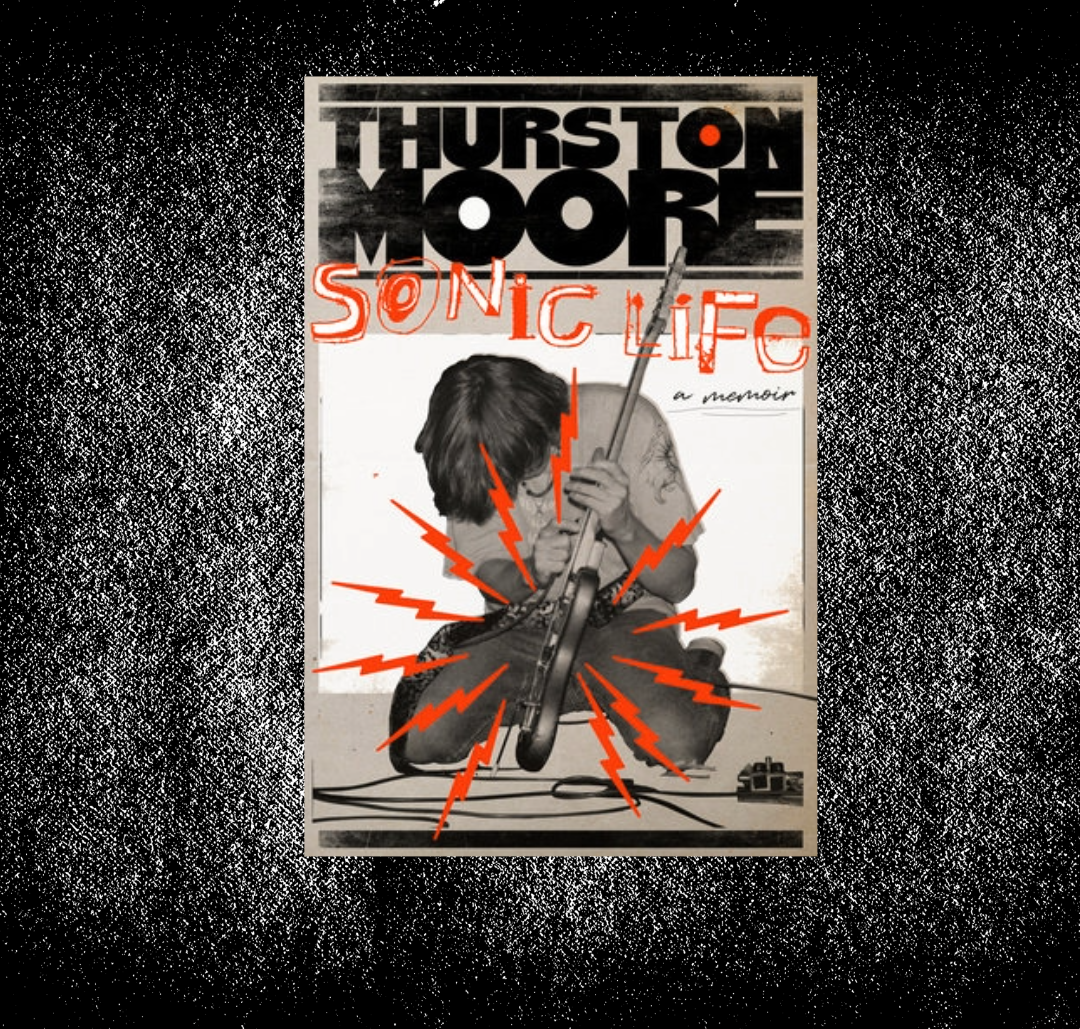

Thurston Moore’s recent memoir Sonic Life is a microcosm of Sonic Youth’s shapeshifting ways. Over the course of the nearly 500 pages, Moore offers up his life arc from a middle-class childhood in rural-suburban Connecticut to his late-teen decision to surrender fully to the art-music vortex of late-‘70s NYC.

The first third of the book is crucial as a pure historical document of the convergence of No Wave, Basquiat, the rising plague of AIDS and how the residents survived and created in what was still essentially an urban warzone. Moore was eager to submerge himself into this overlap of visual, audio and multimedia art, eventually finding a kindred spirit and romantic partner in Gordon, together they formed what became Sonic Youth.

In addition to his work as a guitarist, Moore has been a longtime published writer; his own Ecstatic Peace was an early presence in nascent zine culture. And his skills show. His enjoyment of writing the book is evident and the blur between real/imagined truth is irrelevant to the narrative. Anecdotes and cameos abound. Within a decade, Moore and Sonic Youth were hanging out or working with a roster of late-20th-century creative types, some heroes and others peers. The Beastie Boys, Black Flag, Allen Ginsberg, Gerhard Richter, Patti Smith and a squad of others appear and disappear in Sonic Life.

An endearing ballast of Moore’s tale is his friend Harold Paris. The two met in high school, bonding over the music and poetry of Patti Smith and shared adolescent alienation. The pair would drive down from Connecticut to NYC to see shows at Max’s Kansas City and CBGB. Moore’s recollections of these concerts featuring bands like Suicide and lesser-known No Wave bands are rightfully full of adoration, and it’s apparent these early dips into the weird stream of parallel music had a decisive impact on his eventual life. Paris arrives and eventually departs in Sonic Life, including one passage where he essentially humbles a cocksure New York-ified Moore. Their relationship is a clever device that is a poignant and humanizing facet of the book.

Throughout the book, Moore does not suffer from a confidence deficiency. And that all adds up. Sonic Youth and their precedents, peers and fans-turned-peers—in particular Black Flag, the Butthole Surfers, Minutemen, and later bands like Dinosaur Jr.— were creating music and touring in a time where hostility and indifference were a given, and success was measured by a different rubric. These musicians, and the ever-bizarre Sonic Youth for certain, were working with labels with dicey budgetary practices and even more precarious record distribution. Radio play was limited to college-station bandwidth, and these aforementioned bands were creating their own oases in a desert for their type of music, building and then sharing a network of unconventional rock clubs (Moore gives Jacksonville Beach’s Einstein a Go-Go a shout-out in the book) that ultimately changed the live-music industry. Every vegan safe-space club owes a debt to Sonic Youth and these bands that careened through America in faulty tour vans. Confidence was required to survive the scene that the band was creating in real time.

While some of Moore’s claims on his direct influence on the rock scene are suspect, ultimately his band’s altering of rock music is certain. Every time some post-Creed/Saliva lead guitarist plinks his pick across the tight span of strings on his guitar’s headstock, consciously or not, he is invoking the otherworldly guitar moves that Sonic Youth strummed, clanged and howled into the history of electric guitar. If nothing else, they are the only band who had shared bills with Neil Young and Crazy Horse and Wolf Eyes.

Where Moore is humble is in his acceptance, then and now, of Sonic Youth’s actual chances for popular music success. And those chances are remote. But there was a time when a mention, name drop, even a t-shirt worn by Sonic Youth could benefit up-and-coming bands. They were generous with their affections; whether this was also an assimilation move (see the “Blind Idiot God Effect” above) is really irrelevant. Through Sonic Youth’s strong urging and influence, Nirvana were ultimately signed by David Geffen Company. And the result of that event has now become a well-told rock proverb.

In an utterly admirable career move, after the grunge-jackpot machine broke, at the beginning of the noughties Sonic Youth got even weirder, dropping the rocker trappings that had begun with (and arguably diminished) their 1992 album, Dirty. After headlining the 1995 Lollapalooza tour, Sonic Youth bought their own studio in NYC and began issuing a series of mostly-instrumental self-released records and widening their collaborative efforts. Moore in particular increasingly aligned himself with free jazz and improvisational music.

Moore offers up conditional candor in his book. He is very forthright in some regards, in others more taciturn. In 2011, his longtime marriage to Kim Gordon ended, ultimately also ending Sonic Youth. He addresses the divorce with understandable brevity. While Kim Gordon specifically addressed the breakup in her excellent 2015 memoir, Girl in a Band, Moore is less expansive. Throughout Sonic Life, Moore mentions the word “spirituality” but never really elaborates what he’s referring to. But these are minor gripes. Moore seems more intent to focus on the travelogue of working as a fringe artist from Reagan to Trump, with plenty of bizarre detours on the itinerary.

Now aged 65, Moore remains an active presence. He wrote Sonic Life during the pandemic shutdown, narrowing the final work down from an 800-plus page draft. Since the 1980s, Moore has been featured on hundreds of records, has released dozens of records on his own imprints, still performs regularly and is now a longtime resident of London, where he and his wife Eva Prinz are notable participants in the music and indie publishing community.

Punk rock is now a hashtag but what that concept and term is pointing to is a place that is inherently loser friendly. Punk rock aims to keep the bar low. In many ways it is a term—much like the subsequent steampunk-shoe-cobbler term, Americana—devoid of meaning. But whatever It is, it is based on freedom, solace, formlessness and opportunity. Whether through poetic providence, stubbornness, or DIY shrewdness, Thurston Moore harnessed these forces to an impressive outcome. Sonic Life will arguably appeal to a limited audience and demographic, but for fans of Moore and Sonic Youth, it is a rewarding and captivating read.

Sonic Life: a memoir is out now on Penguin Random House. Click here to purchase it from your preferred book seller.

Mr. Al Pete and Notsucal Release Their Latest Collab, ‘G4.5’

Dinner Party, Tom Misch and More from the Neighborhood with Mr. Al Pete

An Ultra-Chill Playlist from the Latest Episode of Electro Lounge

Sing Out Loud Festival Returns With Hozier, Beabadoobee, Father John Misty, Vance Joy and More

Chicago Alt-Country Faves Wilco Return to St. Augustine with Indie-Folk Great Waxahatchee

Looking for an Alternative to Spotify? Consider Hopping on the band(camp) Wagon

Khruangbin to Bring ‘A LA SALA’ Tour to St. Augustine in April

Perfume Genius, Flipturn, Tamino + Mitski and 6 New Songs to Stream

Song of the Day | “all tied up” by Glixen