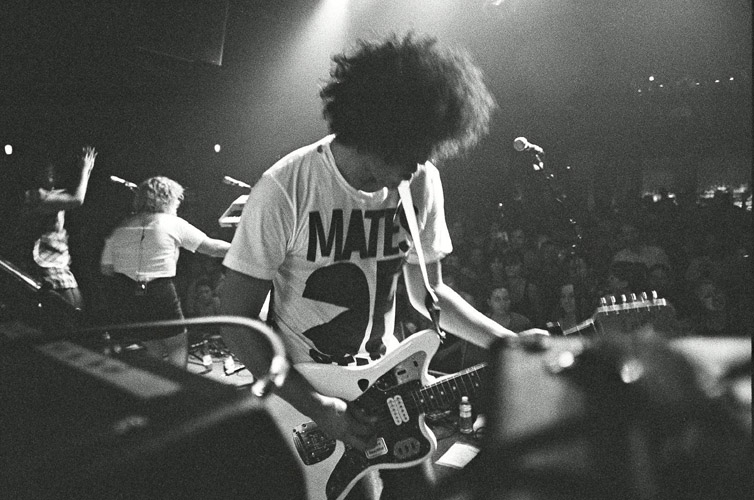

For those asking “What ever happened to Black Kids?” the short answer is that the Jacksonville, Florida-bred indie-rock band is doing just fine.

Black Kids remain a popular and in-demand live act. In November, they’ll play alongside The Cure, Alanis Morissette, Arcade Fire, The Breeders and other generation-defining acts at the Corona Capital music festival in Mexico City. Prior to that, there’s a hometown show on the books – Wednesday, November 15 at the Bier Hall inside Intuition Ale Works.

The long answer, though, requires a bit of context. When the Black Kids – made up of brother-sister duo Reggie and Ali Youngblood, Dawn Watley, Kevin Snow and Owen Holmes – broke out of Northeast Florida and scored international fame in the mid-aughts, the music industry was in a state of flux. Yes, in 2023, the music industry is still inarguably in a state of flux. But the tumult looks quite a bit different than it did in the summer of 2008, when the group’s then-much-anticipated debut long player, Partie Traumatic, cracked the top-five of the U.K. charts, landing the Black Kids on The Late Show with David Letterman and Later… with Jools Holland.

Yes, Coachella was a thing back then; Black Kids performed at the California to-do to much acclaim. As was Pitchfork; the publication named the group’s self-released “I’m Not Going to Teach Your Boyfriend How to Dance With You” the 68th best song of 2007. (For context: M.I.A.’s “Paper Planes” landed at #4.) And there were major record labels; after fielding several offers, Black Kids signed with Columbia Records.

But in many ways, things were quite different in 2007. Spotify was three years away from its U.S. debut. Napster was a thing. Limewire was ascendant, infecting many an unsuspecting user’s desktop with malware. People downloaded music either for free or for $1 per song via iTunes, and synced their music libraries to their iPods or burned songs onto CDs. Major-label artists’ albums were leaked online and upstart musicians uploaded their music into the web’s ether (see: Myspace), all to be consumed by savvy digital sleuths taking advantage of faster (now wireless!) connections.

And then there were the music blogs. The blogosphere – as it was often referred to back then – was insurgent, collectively a threat to the newly vulnerable world of print media. And music blogs, of which there would be many by the early 2010s, emerged as the major tastemakers of this in-flux music ecosystem. At a certain point in the early part of the new century, titles like Idolator, Stereogum, Brooklyn Vegan, AbsolutePunk, PureVolume and Gorilla Vs Bear meant a great deal to independent artists and hardcore consumers of music.

And that’s where the long answer to What ever happened to Black Kids? really begins. Today, Black Kids are perhaps less well-known for what was one of the most-meteoric independent music breakthroughs of the 2000s: the group’s self-released EP Wizard of Ahhhs. Instead, the group is often cited for its similarly swift decline, a trajectory that tracked, over the course of roughly two years, a kind of inverted parabola.

Lately, Black Kids have been cited in several articles revisiting blog rock, a reference to what’s lovingly being remembered as the blog era, a decade-ish-long period that Tim Larew – a former music blogger, himself – calls the “wild west of music distribution and discovery.” During the blog era, a subset of guitar-based indie-rock bands – and rappers – would rise and fall based on the enthusiasm of bloggers. Blog bands like Clap Your Hands Say Yeah, Voxtrot, Tapes N’ Tapes and Black Kids had very little in common, sonically, but they were all more or less unsigned and unheralded before the bloggers found them. As former blogger Ian Cohen put it, blogs served “as talent scouts, PR companies, and the distribution wing” for a generation of bands.

“We were the poster children for a band getting popular on the Internet,” the Black Kids’ Reggie Youngblood told Billboard in 2017.

But the same wild-west ecosystem that built Black Kids up also tore them down. Pitchfork’s review of the band’s major-label debut remains one of the most notorious in a long line of notorious reviews. The publication gave Partie Traumatic a 3.3 (out of 10). Not counting the article’s subheading, the review consisted of one word, “sorry,” and the emoticon “:-/” (emojis weren’t widely used in 2008) over a picture of two pugs. Other music blogs piled on. The record sold poorly and the band parted ways with Columbia at the start of the new decade.

That infamous Pitchfork review may be the last-ever example of a negative music review throttling a band’s success. In 2017, the Wall Street Journal analyzed reviews of 787 albums released that year and found nary a negative word. Fast forward to 2023 and music journalists are literally asking, “Do we need album reviews anymore?” Consider that, a little over 10 years after “Not Going to Teach Your Boyfriend” made music-blog darlings out of Black Kids, Lil Nas X’s self-produced “Old Town Road” hit the top of charts thanks to its popularity among users of the upstart social media app TikTok, many of whom likely don’t even remember music blogs.

Spotify and other streaming platforms have democratized music listening, wresting the tastemaking and curatorial controls from music journalists and putting them in the hands of listeners and playlist curators. Social media, meanwhile, has put much of the work of PR and distribution into the hands of the bands themselves.

It’s in this new era, 15 years after their major label debut, when the term blog rock means little to anyone outside of a small group of music obsessives of a certain age, that Black Kids may finally be able to reframe their narrative.

Blog Rock Darlings

“I kind of got my wish of becoming a cult band,” Reggie Youngblood told me recently. In a long-ranging phone coversation, Youngblood – the band’s singer, guitarist and chief songwriter – spoke candidly about the group’s legacy, more than a decade and a half since they broke the Internet. He was soberly reflective, and at times genuinely amused, chuckling as he recalled the group’s whirlwind rise and fall.

“I see why we may be cited as a kind of definitive band of the [blog rock] era,” he said. “But I always feel like you could just as easily cite the Arctic Monkeys [laughs]. I feel like we’re a bit farther down the list.”

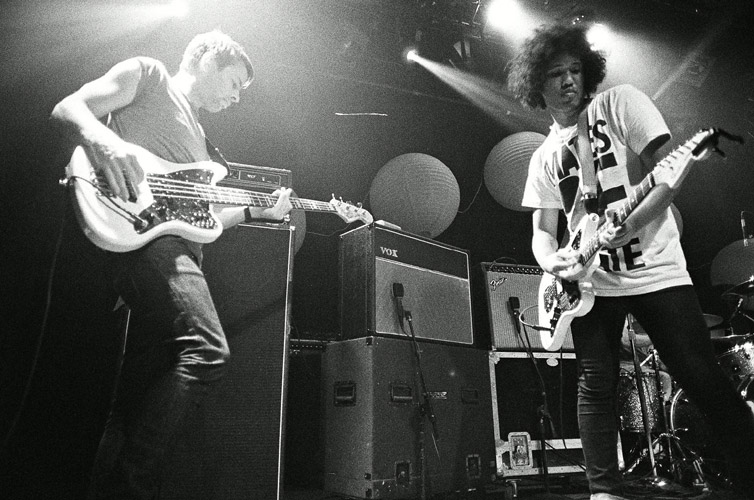

Though the narrative of the Black Kids as an overnight success story is generally accurate, the seeds for the group were planted years before. Youngblood began playing in bands in the late-’90s, and had a short-lived group with future Black Kids bassist Owen Holmes. Youngblood’s sister, the keyboardist and vocalist Ali Youngblood and Ali’s friend, the vocalist and keyboardist Dawn Watley, joined Reggie, Holmes and their high school friend Kevin Snow (drums) around 2006. At the time, the group was just a rough sketch for a dance-forward guitar band.

“For me, I was theater kid so I just thought of it as another project,” says Ali Youngblood, who was 25-years old and playing in her first band when the Black Kids took off. “It just felt like I was having a good time with my best friend. So I was surprised when things took off and there was an opportunity to make this a career.”

The quintet’s shared musical touchstones included Prince, New Order and Daft Punk, as well as popular indie and post-punk acts of the era — Franz Ferdinand, Block Party, The Go! Team, etc. But two now-defunct Downtown Jacksonville locales, the dance venue Club TSI and the eclectic watering hole Art Bar, had just as much influence on the Black Kids’ sound, according to Youngblood. Art Bar, specifically, hosted DJ sets where, similar to the early-2000’s electroclash parties on New York’s Lower East Side, the playlists tended to follow an anything-goes ethos.

“Part of me thinks we were just trying to instill Art Bar Thursday night into an album,” Reggie Youngblood says of the songs that would spark the Black Kids’ formative writing and recording sessions.

The group put together Wizard of Ahhhs and Youngblood uploaded the four-song EP to the social networking site Myspace. Things escalated quickly.

In 2007 Black Kids performed in front of a relatively small crowd at the divey Athens, Georgia venue Little Kings Shuffle Club as part of Athens Pop Fest. They passed out burned CD-R copies of Wizard, some of which got in the hands of bloggers. The blogosphere amplified the group’s reach, directing folks to the band’s Myspace page. Praise from mainstream outlets – including NME, Vice and The Guardian – pushed the fervor up a few decibels.

“It must have been a matter of days,” Youngblood says, recalling the group’s trajectory from the dance floor of Art Bar Thursday Nights to late-night television. “Things happened insanely fast. I wish I kept a diary [laughs].”

The blogs were calling them a mix between The Cure and Arcade Fire (note: when Black Kids play Mexico City this November, both bands are on the bill). Wizard received a score of 8.4 from Pitchfork, who enthusiastically praised Black Kids for making “catchy, tightly executed songs that put a memorable stamp on pop’s classic themes.”

“The timing was perfect,” says writer and music critic John Citrone, who was the Arts and Entertainment editor at Jacksonville alternative news publication Folio Weekly when Black Kids blew up. “Reggie had a real grasp on how to make an earworm. [Wizard of Ahhhs] was super poppy, a mix of retro-‘80s with a synth-pop thing. And Reggie’s so charismatic. He had his own lanky, kind of geekiness that was just really appealing.”

At the time, the group’s name also served to move the needle. The fact that Reggie and Ali are Black, while the other members are white, seemed to confuse some bloggers and blog readers. “It was somewhat controversial,” says Citrone. “People were asking questions about the name and that drove the conversation a little bit. But really, it was their music — this pseudo-retro dance rock — that really worked.”

Consider that, just two years prior to the Black Kids’ debut EP, producer and multi-instrumentalist James Murphy had scored a Grammy nomination by mixing electronic dance music with a guitar-band attack on LCD Soundsystem’s self-titled debut. Artists like MGMT, Peaches and the Kills were borrowing from Britpop, disco and electro pop, giving voice to indie sleaze, an aesthetic steeped in irony and a kind of haphazard efficiency. In 2007, the genre agnosticism that pervades contemporary music production and consumption was in its infancy. Music journalism, which was then still dominated by rockist rigidity, was just beginning to embrace pop as an artform worthy of serious critique.

“Now it doesn’t seem all that unique,” Youngblood says of the group’s sonic fingerprint. “The blogs I was reading at the time, and the music that was being championed, it was an amalgamation of different influences. Although bands had been doing that for a long time, that era just seemed like a more brazen way of doing it.”

For the moment, the rockists seemed willing to wrap their arms around Black Kids. Meanwhile, the group was fielding offers from major labels, and touring at an increasingly breakneck pace. Whenever Black Kids were ready to follow up their EP with an LP, the eyes and ears of the blogosphere were no doubt primed for it.

“There is a dreamlike quality to how it feels to remember those days,” Youngblood says. “I can see images in my head, almost like little vignettes, like ‘OK, we’re talking to XL [Recordings] in London. OK, now we’re talking to Mercury [Records]. These are the dinners. We’re squeezing in shows. We’re playing huge venues and going on these tours. It was a lot.”

Still, as the Black Kids looked to capitalize on their newly earned notoriety, the bloggers and critics of the new media landscape were simultaneously feeling out their newfound power. Before social media, the blogs were deft at driving web traffic. In the era of Gawker, Buzzfeed and Vice, the online conversation was often carried forward by provocation and, occasionally, malice. These were the days of Vice‘s biting “Do’s and Dont’s” column and the proto-trolling of Perez Hilton. In the mid-aughts, when clickbait first appeared in the popular lexicon, Pitchfork was as well-known for turning readers on to new music as they were for taking bands down.

The Review

Upon its release in July of 2008, the Black Kids’ ten-song Partie Traumatic debuted at #11 on the U.K. charts. But many of the same blogs who first championed the group’s EP were less enthusiastic about their first major-label offering.

A Slate article from 2018 cites Pitchfork’s review of Partie Traumatic as an example of a review that had a significant impact on a band’s success. “Officially, the review didn’t end Black Kids’ career. But it certainly knocked it far, far sideways,” wrote Amos Barshard, saying the group’s decline was a “perfect example of Pitchfork’s reach at its most deleterious.”

Youngblood says the band was confused by the Pitchfork review. “I think the review was born out of confusion about our record [laughs]. In turn, we were confused by their review because it didn’t offer any critical feedback. Like, ‘What did we do wrong?’”

Negative reviews appear with less frequency on Pitchfork these days, and when they do they are reserved for bands like the Led Zeppelin knockoff Greta Van Fleet and the unintentionally campy Måneskin – groups whose music is highly derivative and presented with the kind of earnestness and inauthenticity that critics have long reviled. And far from curbing enthusiasm for a band, these reviews – especially the ones that go viral on social media – often have the opposite effect on a group’s popularity. In 2022, reflecting on his viral 1.6-review of Greta Van Fleet’s Anthem of A Peaceful Army, writer Jeremy D. Larson wrote that the response to his review made him realize “his opinion on Greta Van Fleet is largely irrelevant beyond the scope of a few thousand music snobs and select GVF fans.”

Recently Pitchfork began re-evaluating albums that they had previously buried. Among other mea culpas, “Pitchfork Reviews: Rescored” has added points to albums by Prince, Liz Phair, Daft Punk and the Strokes. Pitchfork did not respond to a request for comment on their review of Partie Traumatic or questions about whether or not the album might someday be rescored.

“I see why we may be cited as a kind of definitive band of the [blog rock] era. But I always feel like you could just as easily cite the Arctic Monkeys [laughs]. I feel like we’re a bit farther down the list.”

The Pitchfork review notwithstanding, the band was receiving plenty of positive press. But the release of a major-label debut also carried with it a whole host of performance commitments and other obligations, which Youngblood says were far more responsible for the band’s pending disappearance than bad press or poor record sales.

“I think what actually took the wind out of our sails was the constant touring, constant activity,” he says. “Just going from zero to 60. We didn’t grow up around a lot of touring bands. We didn’t really have a peer group in Jacksonville, or elders, who could say, ‘Tour is going to grind you down.’”

Youngblood says by 2010, morale was low. The friendships among band members were frayed if not broken. “These days, when I hear about artists and bands bowing out of tours, citing mental health reasons, I feel so seen by that.”

“We had gone so hard on the first record, it really did suck the joy out of the group. No one was having fun. That hurt us more than anything.”

Sophomore Rookies

“Reggie’s writing style is very meticulous, very contained,” says musician Cash Carter, a longtime friend of Youngblood’s, and co-founder of their group Blunt Bangs. “There are songwriters who write at a rapid pace. Reggie’s not one of them. It takes Reggie a long time to feel like a song is ready to be released.”

“I have been told that I can be a perfectionist,” Youngblood says with a chuckle. “When we’re doing a song or an album, what I’m hoping for is to not recognize myself in the music. I don’t know if that makes any sense, but if I can erase any sense of myself… I don’t know. It’s so hard to describe.”

“I could sense there was a lot of anxiety” Reggie’s sister Ali says of the pressure to follow up on Partie Traumatic. “I think he was wondering ‘will it be worth it?’ or ‘do people even care still?’ The way people critique stuff, I think they can forget that someone put time and effort and a lot of thought into their art. You can definitely break someone’s spirit.”

The Black Kids all but disappeared from the mainstream music discussion. And whether it was the band’s deteriorating sense of unity or Youngblood’s perfectionism that led to the group’s stasis, a sophomore full length didn’t materialize, which only served to fuel the narrative taking shape at the time that the band was unduly hyped.

As early as 2008, The Guardian asked if the blowback the Black Kids were receiving was evidence that blog-rock acts were being “pushed into the public eye before they’re really ready?” And more recent think-pieces revisiting the era tend to fallback on that narrative, with the previously mentioned 2018 Slate article arguing that, despite all the hype, “The band, to be honest, really wasn’t very good.” Rock critic Steven Hyden was more nuanced in his take, calling the Black Kids’ legacy as the band that Pitchfork ruined “unfortunate.” Hyden argued that the band was no more divisive than chart-topping pop rock groups like Bastille or American Authors. He even called on the band to reunite: “Do it, Black Kids! The world has finally caught up to you!”

In some ways it might also seem like the band’s place of origin worked against them. Blog bands that emerged from, say, the New York City rock scene would always have the cache of NYC to prop them up. Hailing from Jacksonville — not necessarily a highly regarded or even well-known scene — the Black Kids’ inability to capitalize on the buzz of their early recordings likely made them seem flimsy. The era of rock regionalism had long since come and gone without Jacksonville establishing itself as an artistic incubator in the way that Athens or Minneapolis had. And reading between lines of blog posts about the Black Kids from the mid-aughts, any mention of the group’s hometown seems intended to trivialize or condescend — if not simply to play up a can you believe this? quality to the band’s success.

The individual members of Black Kids spent much of the 2010’s working on other projects. Youngblood moved to Athens. Holmes to New York City. When they finally re-emerged in 2017 with the self-released full-length Rookie, they included the infamous Pitchfork review as a coloring book insert as part of the album’s vinyl release.

Rookie received mostly warm reviews. It’s a tight, 10-song collection of danceable indie-rock led by the avant-pop single “Obligatory Drugs,” which sounds like the B-52’s with more sass and more crunch.

“Sadly I think some of the record is just what I think a fan of the Black Kids might want to hear,” says Youngblood. “It comes off as OK.”

Still, with songs like “If My Heart Is Broken” and “All The Emotions,” Rookie features some of Youngblood’s most earnest songwriting, new territory for a band that deployed ironic detachment to great effect just 10 years prior.

By the time Rookie was released, many of the blogs that broke Black Kids had already ceded much of their influence to paid streaming services. Today, hundreds of thousands of listeners stream Black Kids music on Spotify each month, with “Not Gonna Teach Your Boyfriend” continuing to rack up plays, recently eclipsing 33-million streams.

While the blogosphere’s short-lived run as a locus of music discovery was as much a product of the state of technology at the time, certainly blogs represented a kind of potential to infect the masses with a level of enthusiasm for music that was, in the decades prior, only shared by a small subset of music-obsessives. As Peter C. Baker wrote recently in the New Yorker, as a follower of music blogs in those days, “you could feel as if you were a part of something. Something new.”

The majority of the blogs have been diminished or dissolved completely. Vice filed for bankruptcy earlier this year. Now under the banner of Condé Nast — home to such prim legacy publications as Vogue, the New Yorker and Vanity Fair — Pitchfork seems hellbent on shaking its reputation for snark, focussing instead on hefty enterprise features and spotlights on the voices of artists from previously marginalized groups. (Given current questions surrounding the efficacy of music journalism and the ways in which music journalism historically marginalized certain voices, Pitchfork is, in many ways, now a bright spot on an otherwise bleak landscape).

In hindsight it could be argued that music critics abdicated at least some semblance of their importance by embracing clickbait, amplifying their comments sections and publishing wordless reviews like the one Pitchfork gave to Partie Traumatic. Yes, social media’s ability to consolidate the public’s attention sucked the air out of the blogosphere. But the blogs, at their best, certainly offered something more promising and less superficial than an infinite scroll.

While the blogs may have gone dark, Black Kids, the quintessential blog-rock band, endures.

From Blog Band to Cult Band

Last year, for the first time since the Partie Traumatic album cycle, Black Kids returned to the U.K., where Yongblood says they were greeted warmly.

“It was like some people who’d seen us the first time around, but a lot of new people and people bringing their kids, and their kids being like ‘My mom raised me on your music,'” he says.

In November, they’ll use a hometown show as a warm-up gig for their festival date in Mexico City. “All the stuff we do now is because we are very tight friends,” Youngblood says. “And as long as we enjoy each other’s company, we’ll always do something.”

Youngblood says he foresees a third Black Kids album – something with 10 songs, perhaps to be released in 2027, ten years since Rookie. “My OCD insists that we have a trilogy of records,” he says. “I feel good that that’s doable.”

If you took the band’s career – between the EP and subsequent buzz, the major-label debut and backlash, the middling reception to the sophomore album – reordered the signposts and condensed the timeline, the Black Kids’s trajectory would resemble a rather normal arc. When I propose this to Youngblood, he replies with a verbal shrug: “Huh.”

The implications of revising the band’s history in that way would mean Black Kids would occupy similar cultural space as many of their mid-aughts contemporaries. They might be Grizzly Bear or Beirut or TV on the Radio. That is: A good band with some name recognition, but not necessarily a noteworthy one. Instead, they’re either cited as the poster child of a phenomenon or as a footnote to some larger story.

So if it were always Youngblood’s goal for Black Kids to earn a kind of cult-band status, it’s arguable he’s succeeded.

“I’ve always loved rock-history books and music documentaries,” he says. “I knew that the press liking you, then hating you, then liking you again; that’s sort of what is supposed to happen if you’re doing it right.”

Black Kids perform with Luci Lind at the Bier Hall inside Intuition Ale Works in Downtown Jacksonville on Wednesday, November 15. Tickets here.

Mr. Al Pete and Notsucal Release Their Latest Collab, ‘G4.5’

Dinner Party, Tom Misch and More from the Neighborhood with Mr. Al Pete

An Ultra-Chill Playlist from the Latest Episode of Electro Lounge

Sing Out Loud Festival Returns With Hozier, Beabadoobee, Father John Misty, Vance Joy and More

Chicago Alt-Country Faves Wilco Return to St. Augustine with Indie-Folk Great Waxahatchee

Looking for an Alternative to Spotify? Consider Hopping on the band(camp) Wagon

Khruangbin to Bring ‘A LA SALA’ Tour to St. Augustine in April

Perfume Genius, Flipturn, Tamino + Mitski and 6 New Songs to Stream

Song of the Day | “all tied up” by Glixen