Call it ferocity in domesticity rather than fully tamed. Rob Rase is sitting in the home recording studio in the Westside home he shares with wife, Brenda Kato. Sleeved and legged in tattoos, sporting a Rat Town Records t-shirt, Rase grins as he shows off the gear he’s assembled in a relatively short time.

The studio doubles as a practice space for the HC punk band Left On High, a group Rase founded a few years back. He stands up to his full 6’4” height and fires up the mixing board, demonstrating the impressive multi-speaker playback, and a live recording of LOH roars through a series of cabinets mounted overhead along the 22-by-18-foot space.

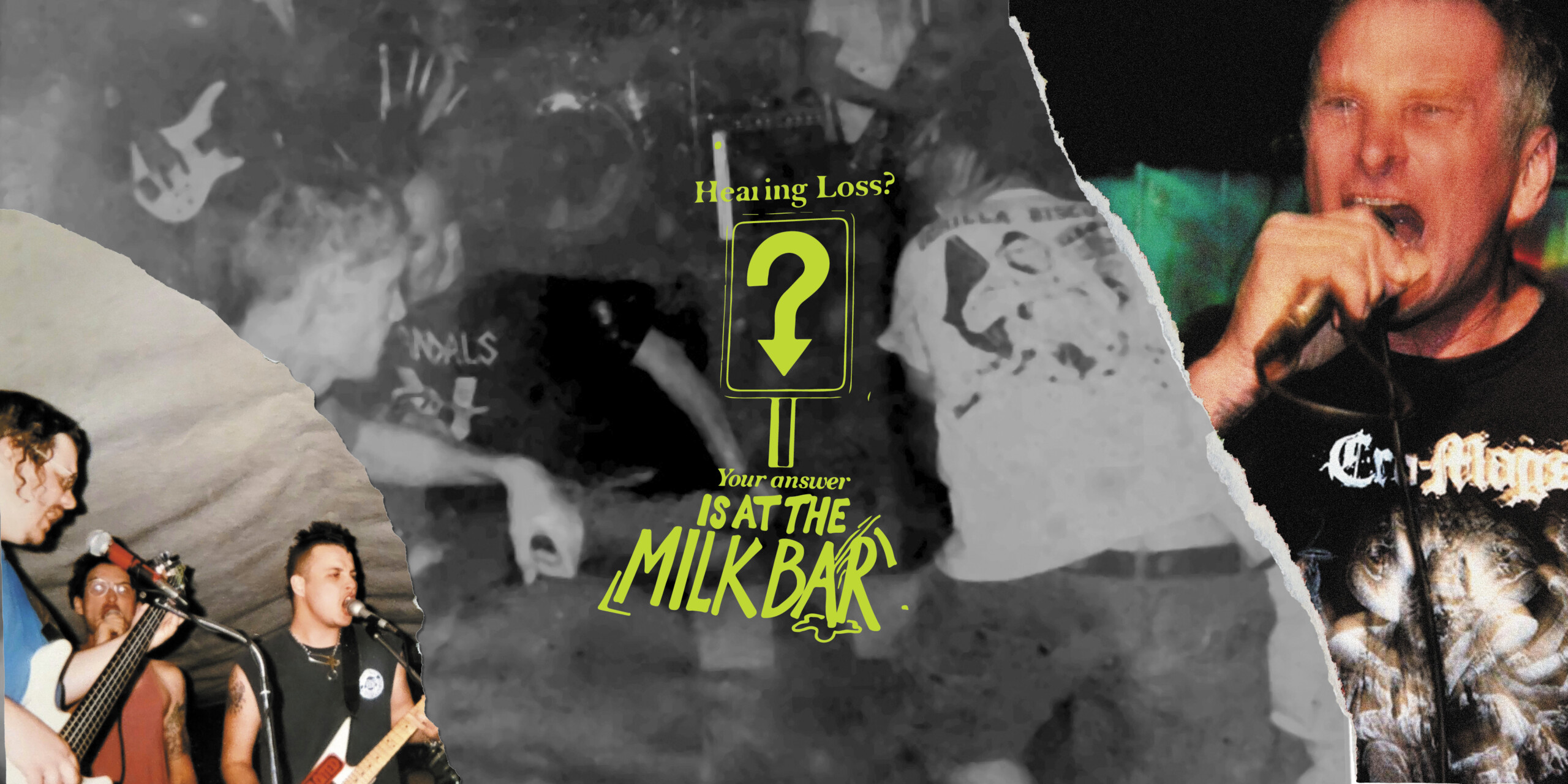

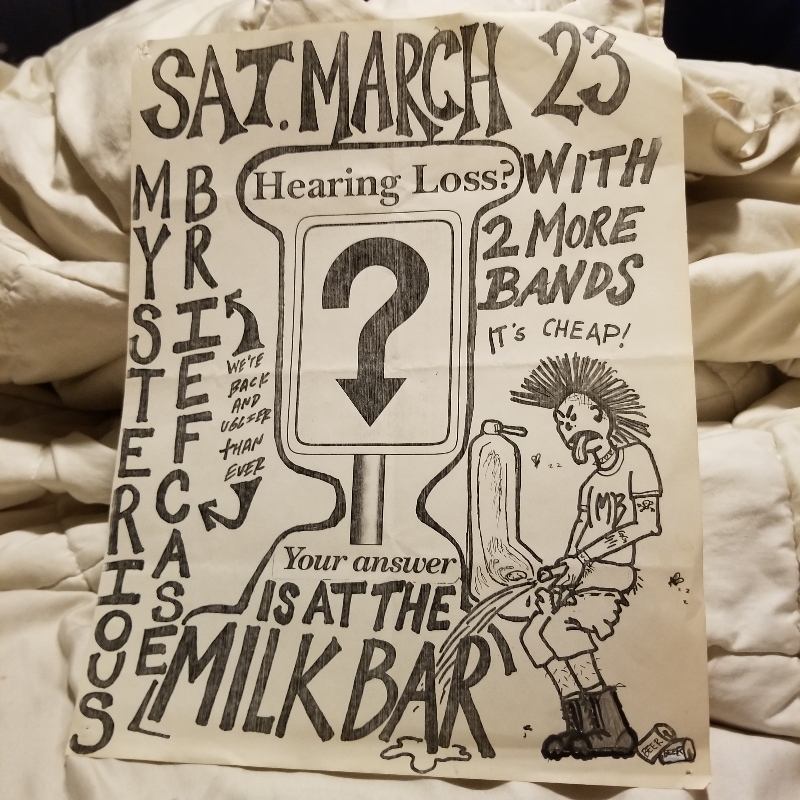

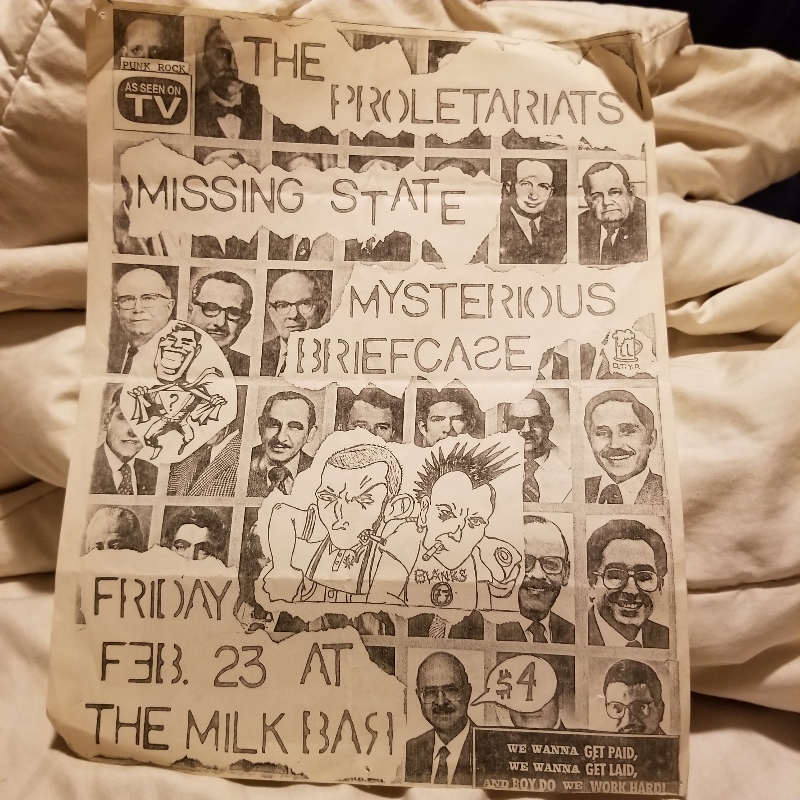

As Rob Society, the now 53-year-old Rase has been a longtime adherent, proponent and participant in whatever Duval County can claim as a truly independent punk-rock scene. Since the mid-1980s, Rase has sang for bands including tenure as a front-person with groups like Secret Society, Pit Stop, Mysterious Briefcase and Asphalt Kiss. For some, these names invoke memories of xeroxed fliers stapled over church bake-sale posters. For others, the names mean nothing.

Like many, before and since in indie music, Rase has been forced to somehow feast in spite of famine as far as budgets for recording. Decades as an artisan-carpenter provided Rob with the blue-collar DIY-skilled tenacity to envision, build, assemble and now slowly decipher and implement, the frustrating nuances of music recording. “We rehearse at least once a week,” says Rase, sitting mere feet from the double-doored, soundproofed entrance into the studio that he designed and installed. “And those practices can go for six or seven hours.”

In addition to Rase on vocals, the current line-up of LOH includes guitarist Tim Eiswirth, bassist Uncle Jesse Edmonds, and drummer Matt Mannucy. The band’s sound is raucous yet solid—more akin to controlled, late-era Poison Idea or Agnostic Front than GBH or Discharge spit-and-splatter.

“I am fascinated by human nature and have been for as far back as I can remember,” offers Rase. “Why I do things, why other people do things…I do not agree with trying to manipulate someone, right? But I am fascinated with influence, and how to properly convey how I feel, and also properly understand how someone else feels.”

That volition is played out in new songs like the dented, jocular anthem of “Summer Daze.” “That is my soundbite view of Florida,” he laughs. “Your mind is made up. We’re terrible. ‘Florida Man.’ Don’t come here.” The cut “Bad at Good” is a paean to the early life of wife Brenda, a longtime local artist, gallery owner, arts advocate and also someone who has maintained a dialogue and friendship with scads of NYHC bands. “She grew up in a certain tradition,” says Rase, with a magnanimous grin, “and she was always told she was being bad and doing everything wrong. She was an artist since childhood and was being split apart trying to push-back on that upbringing. As she was describing this to me, I told her: ‘That’s not bad. You’re not bad. You’re just bad at being good.’”

In the two-and-a-half-minute wake-up call of “Automatic,” the band offers a mosh-ready commentary on the present moment. “Look at how we could drive down the street for an hour or go into work, and never think twice about driving or working. You can’t even remember how you got there. Because you’re on autopilot. And how many things we go through in life without even thinking about what we’re doing. So it can be as simple as that. But it can also be broad as, ‘Why are we doing what we’re doing? What kind of insight do we have? Are we meditating? Or are we thinking? Are you thinking about what you’re doing? Am I going to go with the automatic response and, and react? Or am I going to see the forest from the trees and be able to bring it back in? So it’s really about mindfulness.”

Make no mistake: Rase has arguably spent more of his life in the slam pit than the dharma hall. “I was a feral child,” Rase laughs, of his childhood years in Arlington’s affectionately (and aptly) named Sin City neighborhood. A navy brat, Rase and his family relocated from Philly to Virginia, then Jacksonville. Although he loathed bullying, feudal ranking and approval or rejection for kids in Sin City was measured out in fists and black eyes. “The teachers told my parents: this boy is going feral.”

Like many a wild child, Rase discovered hard rock, even dangerous rock; in this case with the discovery of AC/DC. “Angus Young has horns on the cover of Highway to Hell. Horns! And I was already having to fight everyone in my neighborhood. Ridiculous! You were perpetually out of one frying pan and into the next fire. And I had some intuition that there were other bands like AC/DC. Then I’d see a Molly Hatchet album cover and think, ‘This probably sounds amazing.’ And boy was I wrong!”

Purchasing a cassette copy of Oingo Boingo’s Good for Your Soul cassette at a local Pic N’ Save offered the young Rase a peek into the weird world of new wave and punk. Adolescence kicked the door in.

In high school at Sandalwood, Rase met the punks (“skinheads and death-rock girls”) and heard about the local all-ages venue, the 730 Club. “I never went there because I wasn’t really in the scene. But I remember when The Asexuals played the 730 Club with SNFU, since some kid was wearing an Asexuals shirt at school the next day. And I thought, I need this in my life,” he laughs. His first de facto show was witnessing a performance by local hardcore juggernauts Brutal Assault at a VFW hall on an uncharacteristically freezing Jacksonville night. “I laid my jean jacket somewhere and thought, ‘These people are cool, no one will steal here.” Later that night, while driving home in a car with a broken heater, wearing only a thin t-shirt, his jacket stolen hours earlier by the very punks he had trusted, Rase had an additional unwanted realization. “Welcome to punk rock! These people will also steal from you!”

Petty crimes forgiven, Rase delved into the punk scene and was embraced in kind. Locals like Stevie Stiletto and the Switchblades, War Orphans, Blaine Crews Band and The Creeps were in various stages of prolific-ness and intoxication, self-releasing records and performing at smash-and-grab-style gigs at area dives and hapless rental halls. Record shops like the beaches’ Music Shop (owned by the Faircloths, who also ran Einstein A Go-Go) and Wag’s Record Hound in Orange Park stocked new punk releases. “When I was 16, I was at Coconuts at Regency and was looking through the pricey imports and Thommy Berlin [of Stevie Stiletto] was there. He asked me, aggressively, ‘Who are you?’ I told him I was looking for some punk rock. And he just laughed and said, ‘Oh, boy.’”

When he was 18, Rase formed his first band: Secret Society. “It’s not an exaggeration to say that we could not play music,” he emphasizes, noting that for much of the band’s earliest days, the bass player played a one-stringed bass guitar. Secret Society had a tiny band room but little gear. A PA was out of the question, so Rase would hold a tape recorder in his lap and sing over the din that the band detonated in the rehearsal space. “I sounded like Popeye.” The band had songs like “Blue Light Special,” more of an anti-cop rant than an ode to K-Mart. “We could not play, but we would play.”

“It was so violent in the 1980s. It wasn’t a matter of if someone would get hurt but more about when. There was going to be some blood and invariably some property damage as well. It was sad.”

Secret Society morphed into Pit Stop, which in turn evolved into Mysterious Briefcase, featuring eventual LOH guitarist Tim Eiswirth as well. As the lineups developed due to levels of interest and ability, Rase began playing more actual gigs. Spike’s Doghouse in Arlington, a bar that would seemingly (and refreshingly) book any band, was a crucial proving ground. Opening for 7 Seconds at Metropolis (which eventually expanded as the Milk Bar) in 1989, Rase was a little too eager for onstage dereliction. “I was banned from the club during our set,” he says. [Full disclosure: in 1991, the author was also banned for life after their band Gloryhole played the Milk Bar. Decades after these infractions, Milk Bar co-owner Ed Wilson granted both Rase and the author our respective clemencies.]

Mysterious Briefcase had enough foresight and cash to release two album-length cassettes and a 7” vinyl single. The band gigged fairly frequently and dared to color outside the sometimes-rigid guidelines of hardcore punk. “In hindsight, we were fairly experimental,” says Rase, noting that the band were inspired by more-challenging bands like the UK’s Subhumans. “We had a song called ‘Evolution” that could go on for 15 minutes and have radical tempo shifts.” Rase left Mysterious Briefcase (or the band left him) and in 1998 he briefly fronted Under the Influence, aka UTI.

Then it went dark.

“I was getting too deep down a path.”

In his late twenties, Rase was a dad and worked full time. Just making it into nominal adulthood is a milestone for many who choose the volatile freedom that is as much an element of “punk” than combat boots and a bad attitude.

“I was really just a depressed person. Right? And I couldn’t really even open up emotionally to play a show. I was just lost inside my own brain.” Drug addicts are innately operating on a deficit, whether real or imagined. Why else crave some form of completion? Rase sought maximum integration through drugs, eventually being leveled by heroin.

“The way that I am, the way that my personality is, I’m either all in or I’m not going to do it at all, right? And there was a time when I was sure I was going to be, and was, a drug addict; and I was okay with that. It sounds crazy now but addiction simplifies our lives. Drugs were my best friend and my best friend was kicking my ass, every single day. Yet I loved that relationship but I was just really, really sad. So, I had to turn my back on my best friend.”

Rase detoxed cold turkey and has been clean and in recovery since September 17, 2007. During the interview he was open, loose but when talking about recovery from addiction, he becomes increasingly reflective; visibly humble in a way that is weirdly captured by the studio track-lighting. He concedes that he had stolen drugs and there were “drug dealers wanting to surely kill” him. But the fear of death, sadly and particularly in contemporary America, is rarely the sole motivator to face active addiction head on. Regardless of why he got to where he is, Rase is grateful and emphasizes the “daily reprieve” that is now the crux of his current life.

“I was scared and life was really, really difficult for a long time. I remember one morning when I first got clean, I was walking the dog before I had to go to work, and I looked up at the sky. And it just looked different and I still don’t know how to describe it. I don’t think I’ve ever seen the sky look this way before. And I started looking around. I was like, ‘I don’t think I’ve seen this area, this street, look this way before.’ It seemed unrecognizable; it was a quantum shift. And I was in some different universe, right? I’m fascinated with that, as well: Can we have these parallel universes? Whether it’s real or not, is irrelevant. Yet the concept is interesting. I don’t know what to believe at all. I’m incredibly nihilistic and skeptical when it comes to spirituality. I really don’t care. But that experience was different. And if things were different, I knew that they had changed.”

Rase pursued this different life in the same way he pursued punk rock and narcotics; the proverbial flipping of the script. He became an ardent meditator, got into yoga, trying to show up for others and be of service. Pursuing ego deflation and selflessness in the “look-at-me, follow me” realm of contemporary music might be the most punk-rock move of them all.

“I had—and still have—a great many people that helped me to quit doing drugs. And they helped me by having me watch what they did, right? And by them telling me what they did. Not telling me what to do. But only by telling me what they did and guiding me into a new way of life.”

This weekend, Left On High headline an album release party for The Red Album at Kona Skate Park with FFN and Chalk Tiger. There’s a weirdly bittersweet, both assuring and poignant, closure around the band and this particular show. Rase’s former bandmate and longtime cohort Tim Eiswirth stands side by side with the singer once again, as guitarist for Left On High. While the gig was booked some months ago, local bassist Allison Mathews recently passed away from cancer.

“After I got clean and started playing live music again, Allison and I played together in a band called Asphalt Kiss.” Mathews also played with FFN as well as with the late Ray McKelvey aka Stevie Stiletto. “Allison was a solid bass player, and very private, and a wonderful and sensitive person,” says Rase. “Her death has changed everything and to get to know her was a privilege.”

Why does anyone do anything? Conditioning, boredom, vanity, hunting and gathering? In Ernest Becker’s The Denial of Death, a book that is thankfully way more uplifting than its (punk AF) title, he essentially posits that we are all unconsciously clawing out our legacies. Yet even Becker points that we need, or we desperately concede to, some kind of ethos or calibrating worldview. Much like punk rock. Grandeur and gore aside, life is absurd. Punk rock is highly absurd and surviving addiction and punk rock is absurdity at the level of cosmic comedy.

Three albums in, Left On High has surely moved beyond a “project.” While the band has yet to play out of this area, they’ve shared bills at local clubs like Jack Rabbits, Rain Dogs and Archetype with punk greats like Sheer Terror, Antiseen, and Murphy’s Law. Even though Rase is the only remaining “founder” of the band, he assures me he still only holds “one vote”— even though I imagine the band would prefer to cast all ballots in his air-conditioned, safe and secure home studio that even boasts a private bathroom.

“You know, I’m really comfortable talking about music, and definitely recovery from addiction, but I don’t put my business on the street, you know?” It’s a question that seems addressed more to and from Rase, rather to the stillness in the room. He’s enthusiastic about music, especially the evolution and safety of the punk scene. “It was so violent in the 1980s. It wasn’t a matter of if someone would get hurt but more about when. There was going to be some blood and invariably some property damage as well. It was sad.”

He recalls an earlier show at Kona, when he hurled his giant body into the crowd and was caught, carted around, and returned to the stage by a group of teenagers, mostly teenaged girls at that. “I don’t know why I basically charged a crowd of girls,” he laughs. “I’m a dad. I bet some parents were horrified.

“But there is a definite symbiotic energy when the music is really right. You know? At 53 years old. I’m having more fun than I’ve ever had my life. I’ve had more fun playing music, and not taking drugs, than I’ve ever had in my life. On stage is who I am, right? I can cut loose; I can do anything I f***ing want to do. I can run around. I can say what I want to say. I can say what I mean. When I am offstage, I have to watch what I say. I have a job that I have to watch what I say I have to be very careful. I have to be strategic. So the positives of my life now far outweigh the negatives; especially considering how I wanted so badly to be negative.”

Left On High hold a record-release party for The Red Album with FFN and Chalk Tiger on Saturday, April 8 at Kona Skate Park in Arlington; the show is all ages and more info is available here. You can follow Left On High @leftonhigh and check out music and upcoming shows here.

Mr. Al Pete and Notsucal Release Their Latest Collab, ‘G4.5’

Dinner Party, Tom Misch and More from the Neighborhood with Mr. Al Pete

An Ultra-Chill Playlist from the Latest Episode of Electro Lounge

Sing Out Loud Festival Returns With Hozier, Beabadoobee, Father John Misty, Vance Joy and More

Chicago Alt-Country Faves Wilco Return to St. Augustine with Indie-Folk Great Waxahatchee

Looking for an Alternative to Spotify? Consider Hopping on the band(camp) Wagon

Khruangbin to Bring ‘A LA SALA’ Tour to St. Augustine in April

Perfume Genius, Flipturn, Tamino + Mitski and 6 New Songs to Stream

Song of the Day | “all tied up” by Glixen