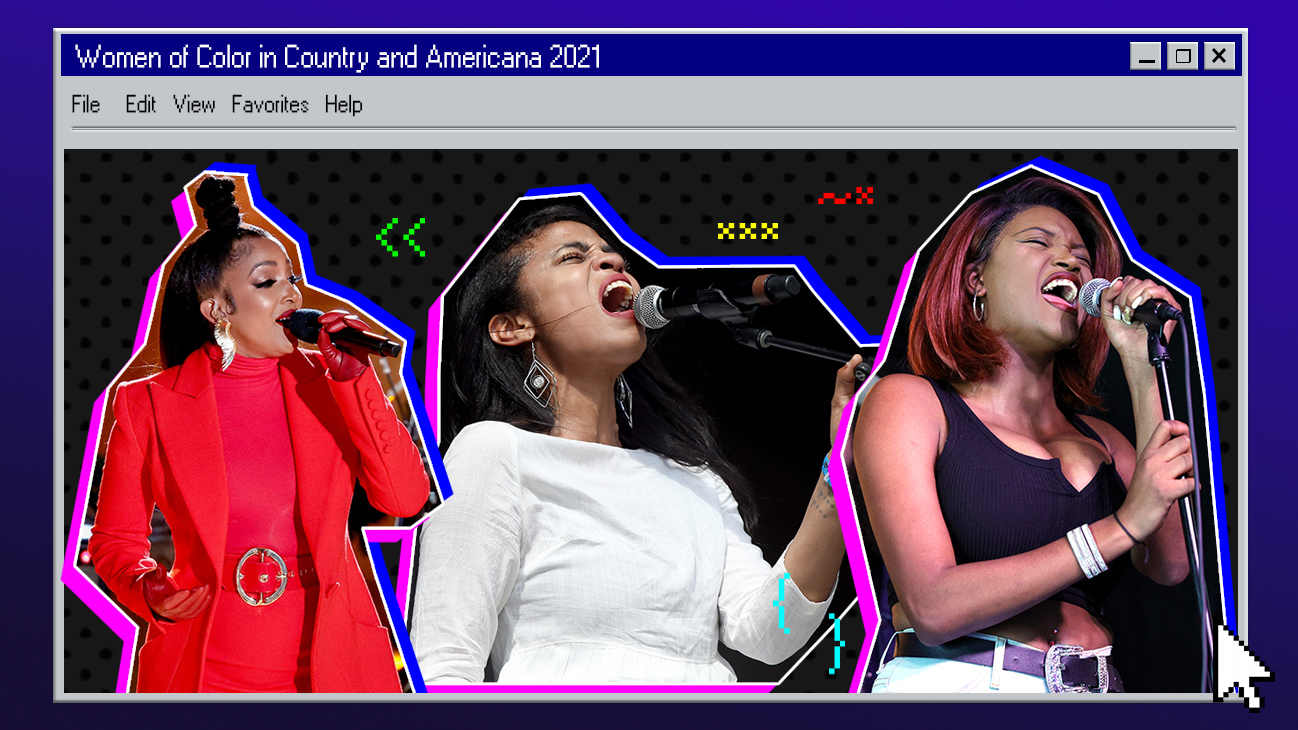

If 2020 was the kickstart of a reckoning—of country/Americana music (and, really, all of America) being forced to come to terms with its history of racism and exclusion—2021 was the year of reclamation. Even as sustainable, systemic change remains elusive, Black women, in particular, have leveraged the power of streaming platforms and social media to bridge the chasms previously carved by labels, publishers and radio. This year, as listeners clamored for playlists and show lineups that actually mirror the world around them, these women built brands and fanbases, all the while hoping to make the industry a more welcoming place for others who look like them. Our timeline, far from exhaustive, charts some of the ways it happened.

January

The folk lane that Yasmin Williams occupies—solo acoustic guitar—is often overlooked in accounts of sexism and racism in roots music, but it too has been dominated by white men for the last half-century. With the compositions on her January album Urban Driftwood, and the ways she performed and talked about them, Williams breezily intervened in those narrow notions of musical lineage. Her fingerstyle picking virtuosity entails being open to effervescent and thrillingly unconventional techniques.

Rissi Palmer, on the other hand, intervened closer to the mainstream. She started applying lessons learned through her dehumanizing experiences in the country music industry to advocacy in 2020, with the launch of her galvanizing Apple Radio show Color Me Country and an artist fund of that same name. The first month of 2021, she announced the inaugural class of Black women artists that she wanted to amplify (Camille Parker, Kathryn Shipley, Julie Williams, Ashlie Amber, Kären McCormick) and accelerated her efforts to disburse microgrants. Palmer’s style of reaching out to fellow artists of color with solidarity and assistance would serve as a template for so much other informal network-building throughout the year. —Jewly Hight

February

Amythyst Kiah‘s time in the group of banjo-playing, Black women assembled by Rhiannon Giddens, Our Native Daughters, helped thrust Kiah into a national spotlight, especially via a composition she contributed to the group, “Black Myself.” Kiah staked out her artistic individuality by rerecording the song’s historically knowledgeable and thoroughly current assertion of Black humanity as a brusquely bluesy Appalachian alternative rock tune. That was the first glimpse of how she’d bring together old-time leanings and eerie atmospherics on her album Wary + Strange to create a world big enough to house her storytelling.

A few days later, speaking on a virtual panel presented by Nashville Music Equality, Frankie Staton and Cleve Francis recounted their much earlier efforts to make room for themselves and other Black country artists in the format, work they would also soon discuss on an episode of Palmer’s show. When they described the industry advocacy they undertook through the Black Country Music Association in the ’90s, they weren’t just strolling back through history—they were sharing strategies that new generations of artist-activists were hungry to hear. —Jewly Hight

March

Via her Color Me Country Apple Radio show and fund, the Rissi Palmer of 2020 and 2021 is best known as an activist fairy godmother, the wise and benevolent matriarch of the movement. But in March, with her first appearance at the Grand Ole Opry in 13 years (on the same day she made her debut as a correspondent for Country Music Television, no less), Palmer reminded us that she is an artist, too—and a damn good one. Miko Marks also made her artistic reemergence that month after industry roadblocks forced her out of the industry and back to her Bay Area home in the mid aughts. Our Country is a masterful amalgam of Southern musical traditions and a perfect accompaniment to roots-rooted releases from Valerie June (The Moon and Stars: Prescriptions for Dreamers), Sunny War (Simple Syrup), and Queen Esther (Gild the Black Lily). —Andrea Williams

April

Holly G‘s motivation for launching The Black Opry, an online platform highlighting Black artists in country and related genres, was simple: “I was exhausted with the culture of country music not ever creating space for people who look like me,” she says. “Both artists and fans are shut out from the industry, so I felt like it was important to create a space where we felt safe and welcome.”

Adia Victoria also understands the importance of the communal, of making and listening to music, of honoring the past while making room for the present. Victoria launched Call & Response in April; her first guest on the podcast was musician and self-proclaimed “armchair historian” Rhiannon Giddens. Giddens’ work has long sought to re-center Black people and Black innovation in the narrative of American traditional music, and her newest album, They’re Calling Me Home, is no different. Released April 9, the album highlights the musical roots of both Giddens and her Italian partner/collaborator Francesco Turrisi, as well as their adopted Irish homeland. —Andrea Williams

May

Outside Child – Allison Russell‘s May-released and critically mega-acclaimed album – gave musical form to fierce honesty and emotional freedom while featuring strong songwriting and virtuoso musicianship. Her lifelong struggles with being an “outside child” — as in one born out of wedlock — define the album’s redemptive storytelling. This includes her unpacking a youth defined by being a runaway from her Montreal home and a sexual, physical and psychologically abusive adoptive father, coupled with a beautifully-unveiled tale of discovering freedom in her sexual identity. Given their genteel beauty and soulful gravitas, songs like “Persephone” and “Nightflyer” resonated with critics and fans alike for over six months on the Americana charts. This, because they acknowledge and reach beyond the manic-depressive double-bind of representing so many queer listeners’ rarely discussed (and thus deeply traumatic) human truths. Russell’s album inspired a metaphorical metamorphosis in listeners where tears washed away sadness, yielding unfettered rainbows and broken psychological bonds in its wake. —Marcus Dowling

June

In an industry that has both a race and gender problem, it’s not surprising that Linda Martell is still relatively unknown. Even as the spotlight shifted to a smattering of young, Black female country artists in 2020, there was little celebration for the one who preceded them all—or the 50th anniversary of her groundbreaking album Color Him Father. That changed in June 2021, when, just days after her 80th birthday, Martell received the Equal Play Award during the CMT Awards. Martell’s influence is everywhere, of course—in mainstream country, but also on its periphery, where artists like Amythyst Kiah and Joy Oladokun merge their experiences and singular aesthetics to create a take on Southern sonics that is all their own. On Wary + Strange, Kiah’s vibe is hard, heavy, and blues-inflected, her voice soaring and powerful as she stands boldly in her uniqueness. Oladokun takes a more subdued approach on in defense of my own happiness, but understand: the sweetness of her melodies and acoustic accompaniments are an indication of vulnerability, not passivity. —Andrea Williams

July

Since Bob Dylan played folk music with an electric guitar there in 1965, the Newport Folk Festival has showcased intentional moments of sustainable sea change in popular music. Thus, Allison Russell curating the main stage on the 2021 festival’s final day—and highlighting her long-time Black female musical friends, essential non-Black allies, with the legendary Chaka Khan in the place of honor—drove home the point that as a sociopolitical bellwether, the spaces created by Americana and country music eparational gender and racial equity. Also, British-Caribbean star Yola—who appeared on that stage—released the “genre-fluid ” album Stand For Myself. On that recording owing as much to American Bandstand (or Soul Train) in 1971 as to the current roots music scene, Yola drove home the point that the mood in Americana had (positively) changed. —Marcus Dowling

August

Black women are undoubtedly a dominant creative force in country and Americana, but they are far from a monolithic lot. By late summer 2021, pop-country performer Tiera had turned two years of mounting buzz into a label deal with Big Machine Records. Moreover, New Orleans, La.-by way of Poplarville, Miss.-based familial trio Chapel Hart released the indie-favored The Girls Are Back in Town. This rocking Nashville album counts heartbreak, cheap whiskey, and Dolly Parton among its inspirations. And, yes, trans femme producer Lafemmebear (alongside fellow trans femme instrumentalist Mya Byrne) was requested by Reba McEntire herself to craft a country-trap remix of the “Fancy” vocalist’s timeless hit “I’m a Survivor” for her Revived Remixed Revisited triple-album. The expansion of diversity and visibility for Black women did not delay the continued movement towards Black women’s social and musical progression in country, Americana, and related genres. —Marcus Dowling

September

A decade is too long to wait for any debut, but with the release of Remember Her Name, Mickey Guyton more than made up for lost time. The album begins with the title track—a powerful, driving midtempo that lays claim to the legacy Guyton planted in 2011 and saw bloom during the tumult of 2020—and culminates with an updated version of 2015’s “Better Than You Left Me,” the coulda-been-hit that first marked the story of a grateful ex and now reveals the full-circle maturation of a woman who refuses to be confined—or defined—by industry rigidity.

September also saw the release of Adia Victoria’s third album, A Southern Gothic. Building on last year’s yearning yet declarative “South Gotta Change,” the South Carolinian blueswoman continues to display her devotion to the South while also challenging it to be better. This juxtaposition provided the foundation of numerous panels during 2021’s AmericanaFest as Victoria, Allison Russell, Miko Marks, Queen Esther, and others shared their experiences creating music they loved—and their desire for the industry to love them, fully, in return. —Andrea Williams

October

With her October album Americana, Lilli Lewis made a statement not only about her ability to refine and expand roots forms like murder ballads, a cappella spirituals and singer-songwriter storytelling with transformative empathy and classically trained poise, but also about how she’s learned to bridge racially segregated cultural and musical worlds over her lifetime. No sooner did she stake her out her place in the scene—on the authority of mastery, as opposed to industry support (she practices resourceful independence with her tiny, Louisiana label)—than she had to contend with a kind of erasure. Reps for the white, country-pop trio who’d claimed the very name of longtime Seattle blues singer (and Black women) Lady A as their own moniker in 2020 got Lewis’ album temporarily pulled from Spotify, because it featured the original Lady A as a guest. But Lewis fought successfully for her project’s return to the platform.

That same month, Miko Marks reinforced her return to the spotlight as a commanding roots performer with her second release of the year, the spirited and historically savvy Race Records EP, and Mickey Guyton performed her blazing power ballad “Remember Her Name” the night she was honored as CMT’s breakout artist of the year, with Yola supplying full-throated support as her duet partner. —Jewly Hight

November

By winter’s onset, the consistency of calls for accountability in sustaining equity for minorities and women in equal measure began to yield profound rewards. Notably, onstage at the 2021 Country Music Awards, Mickey Guyton was joined by Brittney Spencer and Madeline Edwards in her performance of her Remember Her Name track “Love My Hair.” The magnificent performance continued the year’s trend of proudly defiant presentations of Black femininity making respected space for themselves in country’s mainstream. In a similar vein, at the Country Music Hall of Fame’s medallion ceremony, Spencer’s performance of Dean Dillon’s canonical country ballad “Tennessee Whiskey” not only caused a standing ovation, but gained immediate praise from iconic country stars like Brenda Lee and George Strait.

Also, 2021’s Grammy nominations proved portentous of more to come. Mickey Guyton’s sole nomination in 2020 was tripled in 2021—her finally-arrived debut album Remember Her Name yielded nominations for best country album, song and solo performance. Allison Russell’s breakthrough year as an artist and activist led to nominations for best American roots album, performance and song. Yola received her fifth and sixth overall Grammy nominations ever for best American roots song and album. Rhiannon Giddens received two nominations to add to her six previous nods and one win. And ethereal singer/songwriter Valerie June earned—for a duet with legendary soul vocalist Carla Thomas—a nomination for best American roots song. Intentional efforts aimed at accountability, reparation, and elevating creative excellence are now leading to unprecedented, expansive successes at the industry’s pinnacle. —Marcus Dowling

December

The grassroots networking that gathered momentum throughout the year and drew artists, activists, advocates and academics into robust collaboration culminated in December in the second virtual edition of the Country Soul Songbook Summit, with its welcoming, nautical theme of All Aboard the Sea Change. Not only had Black Opry founder Holly G joined artists Kamara Thomas and Kym Register and community organizer Heather Cook on the conference planning team, but they’d lined up panels and performances—summed up on the flier as “future-minded conversations and subversive offerings”—that reflect the true range of BIPOC and LGBTQIA folks and allies working to transform roots music, both inside and outside the industry.

A week later, the touring Black Opry Revue, a package show that unites experienced performers with those new to bigger stages, will play its first Nashville date, with Frankie Staton as resident elder and special guest. And these events bring 2021 to a close with multiple generations of Black women visionaries leading the transformation of roots and country spaces. —Jewly Hight

This timeline, like the overstory of a verdant forest, thrives through its multitude of entrenched, fruitful roots. Alongside the multitude of artists and activists mentioned, these artists listed below also were impactful creatives in 2021: Ashlie Amber; Joy Clark; D’Orjay The Singing Shaman; Evil; Kam Franklin; Stephanie Jacques; Roberta Lea; Kären McCormick; Wendy Moten; Camille Parker; Lizzie No; Reyna Roberts; Sacha; Julie Williams.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))

Mr. Al Pete and Notsucal Release Their Latest Collab, ‘G4.5’

Dinner Party, Tom Misch and More from the Neighborhood with Mr. Al Pete

An Ultra-Chill Playlist from the Latest Episode of Electro Lounge

Sing Out Loud Festival Returns With Hozier, Beabadoobee, Father John Misty, Vance Joy and More

Chicago Alt-Country Faves Wilco Return to St. Augustine with Indie-Folk Great Waxahatchee

Looking for an Alternative to Spotify? Consider Hopping on the band(camp) Wagon

Khruangbin to Bring ‘A LA SALA’ Tour to St. Augustine in April

Perfume Genius, Flipturn, Tamino + Mitski and 6 New Songs to Stream

Song of the Day | “all tied up” by Glixen