Tracy is wearing a plain, worn, black T-shirt, no pockets, no sly sayings, and I imagine her waking up in it, in just that T-shirt, and walking around my small basement bedroom in the Oakland split-ranch that I am sharing with 5 other grad students for $200 dollars a month each, so cold we can see our breath. Tracy is getting me a glass of water from the bathroom, brings it to me, sitting down beside me, and her legs whisper secrets before they fold beneath her. Her brown legs gleam—has she used up the last of my lotion? Tracy sings to me: revolution, problem fathers, fast cars, being jailed for who she loves. Tracy is bold, but looks away from me as she sings. Her smile is a shy secret in the dark. Tracy’s hair sparks in a million different directions. She is wired to the sun.

Watching Tracy Chapman, and listening to her 1988 self-titled debut album, helped me say what I hadn’t yet said out loud.

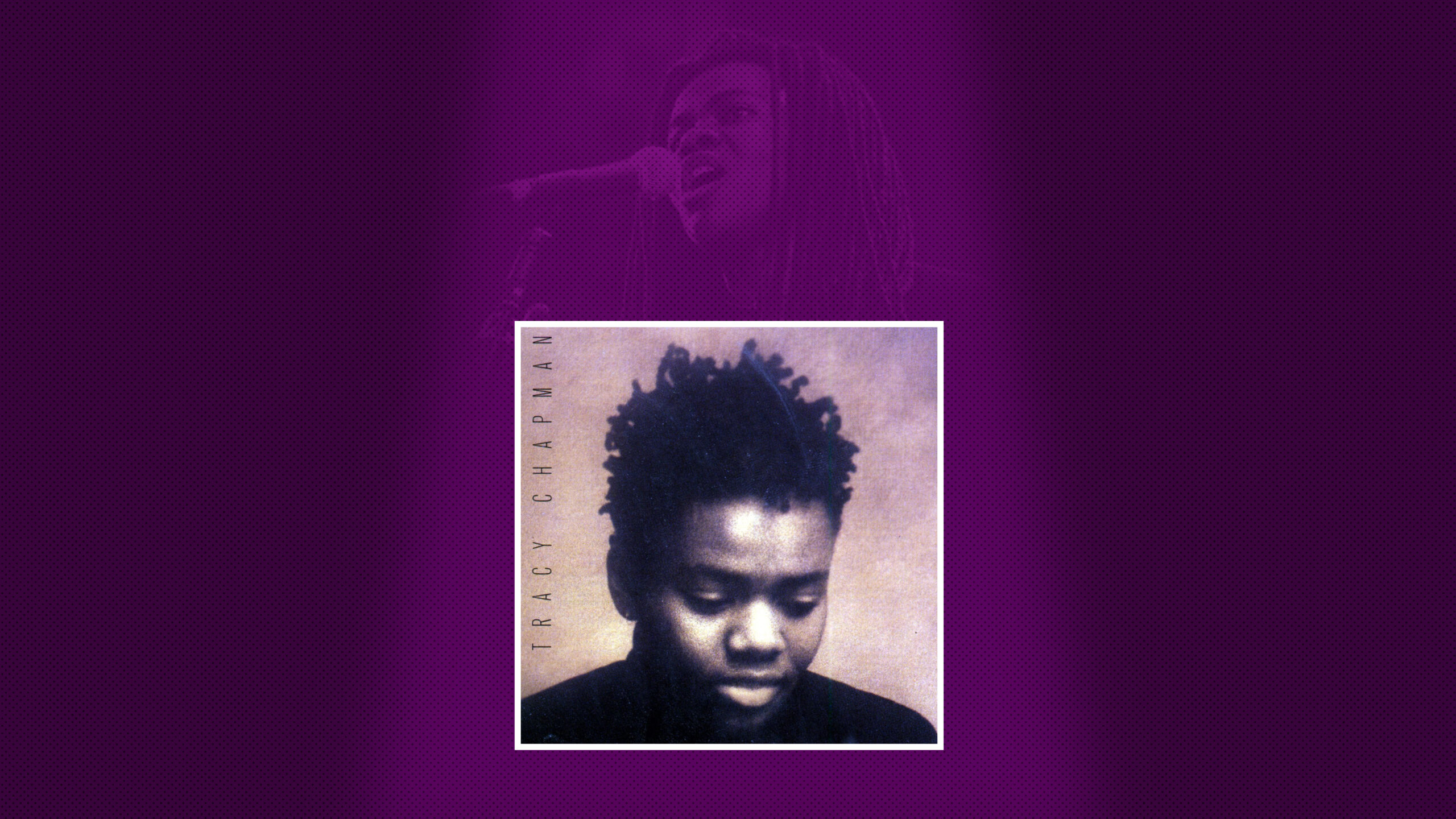

For a brief while after the release of the album, Tracy Chapman occupied my dreams –and perhaps everyone else’s. She was everywhere in pop: on Saturday Night Live (twice); touring with Sting for Amnesty International, celebrating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; in concert at The Oakland Coliseum. At age 24, plucked from a coffee house near her college campus for her sincerity and stage presence and chops and offered a contract by Elektra Records, Chapman became a star, albeit a reluctant, or at least a quiet, one. Tracy Chapman captured the attention of the world with these 11 songs of struggle, resilience and survival, without cleavage, without choreography, without bling.

I remember watching Tracy Chapman perform “Fast Car” on a live broadcast from London’s Wembley Stadium for Nelson Mandela’s 70th birthday in June of 1988. Like many of us around the world, that was the first time that I had seen her perform. Legend has it that Chapman had been called on stage to perform her songs after Stevie Wonder ran into a glitch with his technology. Chapman, armed with only her voice, an acoustic guitar and a microphone, was the woman for the job. But it was a daunting one.

The day is windy, the audience well-meaning but restless and huge. We watch as Chapman steps up to the mic and takes stock of the audience: some paying attention, some waving their banners, some wandering the aisles. Chapman’s eyes seem to water — perhaps from the wind, or perhaps in response to the enormity of the task at hand. She takes a breath and begins. For the first lines, her voice is a tad off key, a little shaky, but then she gains momentum as the story takes over: her narrator yearning for a better life, for speed and freedom and escape from drudgery and exploitation. Through voice and gesture and the power of her eyes, Chapman transports us, letting us feel vicariously the narrator’s cycles of yearning and disappointment.

Watching from my undergraduate dorm room as I prepared for graduation and my move to graduate school at UC Berkeley, Chapman’s presence felt like a miracle. I remembered a feeling that I hadn’t had since I first watched Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It with my all-white group of friends in Kansas a few years before — that the ancestors were sending me a gift: the chance to see and hear myself onscreen, to help me get through the hard times ahead.

***

In cadences, beats and attitude that seemed to draw equally from Women’s Music queer sheroes like Joan Armatrading and Bernice Johnson Reagon, the fighting power of reggae greats like Peter Tosh and Bob Marley, the full-throated, the earnest elegance of folk icon Odetta, Johnny Cash’s Man in Black outlaw spirit and a little bit of Sting’s smoothness, Tracy Chapman tells stories of everyday lives where injustices were named, and the complexity of survival was explored feelingly, through storytelling. “Fast Car,” “Behind the Wall,” and “She’s Got Her Ticket” make up trilogy of women’s struggles against domestic violence, each exploring a different outcome: narrow escape, continued harm, transcendence. In “Behind the Line,” Chapman sings of the segregation and raced-based riots that have scarred cities and towns for the last 200 years; in “Mountains O’ Things,” she steps into the mind of a greedy capitalist who seeks to blunt his own loneliness with consumption, at the cost of others’ lives; in “Talkin’ Bout a Revolution,” she gives voice to the rise of a people’s movements around the world.

“Fast Car,” perhaps the most well-known song on the album, tells a compelling story of yearning shaped by surviving intergenerational violence, and that ways that class, among other things, shapes and limits women’s choices. The landscape of the song seems consummately American (the open road as a space of potential and reinvention; landing at the dead-end space of the supermarket as a checkout girl, with a bar and friends as the only escape). But unlike the white masculinity of Bruce Springsteen’s storytelling, which covers some of the same territories, I didn’t have to imagine myself as a white man to be transported into the song. I could imagine her lover as any gender, and I could imagine them as Black, or Latinx or white. This is a product of Chapman’s powerful lyrics and embodied performances, including her ability to capture the inner thoughts of her heroes — their process of discovery.

But some of the power of this and other songs on Tracy Chapman was more personal. Tracy reminded me of myself. Her dreadlocks did not look like dreadlocks created at a beauty shop (and at that time, it was hard to find a beauty shop who could do them). Hers, like mine, were solidly DIY — where you can see the nappy edges and strong roots twisting themselves before your very eyes. Her boxy black turtlenecks and T-shirts looked like they had been washed and worn many times, and chosen to hide curves. Her stance was shy, eyes sometimes closed or hidden, until the drive to answer the questions that she was singing about drove her to look at us directly.

This was the music that I needed at a time when I felt pressure to know everything before it was taught, where I felt the limits of others’ assumptions of me most keenly. In graduate school, I often felt like an imposter. The elderly white professor in the first-year course that served as an introduction to graduate school confirmed my fear for me one day in my first semester, as I sat on the wide concrete steps of the English building, soaking up some sun before classes. Standing close, his baggy suit pants leg at my eye’s view, he bent down to pat me on the head. “You’re a wonderful young lady, Francesca,” he said, smiling at me like one might smile at a pet. “But you may not belong in graduate school.” Kay, the graduate program administrative assistant, a total badass who seemed to hold the keys to the kingdom of the English department, frequently confused me for Eleanor, the other Black girl in my year, a brilliant and wildly accomplished Alice Walker scholar. In this era, Affirmative Action opened doors while subtly reinforcing the contingency of the bargain.

I was the only Black Shakespeare nerd; a proud land grant State University graduate in the company of Ivies; an introvert training for a profession that demands that you, well, “profess.” And I was queer, and until Tracy Chapman, hadn’t quite seen myself in the media around me. I was not white, not butch, not femme, sometimes fluid in who I fell in love with. I found My Beautiful Launderette more relatable and far more hot than The Children’s Hour. I mean, I felt queer, but was I really? Despite some major girl crushes throughout my childhood and young adult life, a bit of flirtation and occasional sapphic footsy under the table at my favorite gay bar, and one memorable girl on girl bathroom make-out session, technically, I hadn’t ever had sex with a woman.

Chapman herself has been a bit of an enigma, private about her sexual identity until her one-time romantic partner Alice Walker disclosed their relationship in the 1990s. But those of us with our gaydar activated knew what we knew. For many, “Fast Car” felt like a lesbian anthem, a desire to escape from small town drudgery and heteronormative life. And “For My Lover,” on the second half of the album, sang deliciously of an outlaw love. With the twang of Ed Black’s steel guitar and Chapman’s tough-girl contralto, the song moodily discloses the trials of a love that is deemed criminal and dangerous by society’s standards:

Everyday I’m psychoanalyzed

For my lover, for my lover

They dope me up and I tell them lies

For my lover, for my lover.

This resolute trickster lover shares much in common with the LGBTQ folks, especially folks of color, who have been arrested, institutionalized, blacklisted, fired from their jobs, cast out of political organizations and murdered for their gender expression, sexual desires and choice of sexual partner in the 20th (and 21st) century. But the narrator refuses a story of tragedy, willing to risk it all for love and “you, you, you, you, you.” In this song, and in the other intimate final songs on the album, Chapman avoids explicitly gendered pronouns, in favor of “baby” and “you.”

Maybe Chapman was somewhere between Prince, who knew for sure that he wanted to be your lover, and “your mother and your sister, too” (in “I Wanna Be Your Lover”) and Michael Jackson, tortured by his “damned indecision and cursed pride” that made him keep his love “locked deep inside” (in “She’s Out of My Life”). Or maybe she just had other things that she wanted to do than discuss her sexual identity in those years. In the tension between the determination of the first songs on the album, and the more personal, veiled stories of love in the last ones, Chapman captured the flow of feelings that I felt, both hyper-visible and invisible as a Black woman in a white space, and still in formation in my own identity — as blurred as that fuzzy image of Chapman on the album cover. What I needed was some space in-between, just to think. Tracy Chapman created that space of protection, confirmation and contemplation as I figured out who I was, rather than just who others wanted me to be. Given the pressures that I was feeling, especially in graduate school, to “represent,” that indeterminacy was a pleasure. Tracy Chapman for me dramatized the space on the verge of action, where desire begins to crystalize. That crystallization can absolutely happen in the moment of singing, when I was all alone in my room, matching my voice to Chapman’s as she digs into those last lines of each song.

Listening to Tracy Chapman, I found the power of uncertainty as both a space of discovery and perhaps a destination in itself. In the company of her music, perhaps I could both know what I know and be open to the flux at the heart of queer identity.

Later that summer, when I came back home to Chicago for school break, I told my mother that I was queer at the International House of Pancakes in Boystown, Chicago’s gay neighborhood, where she lived. My mother, who knew me better than anyone, told me, “I already knew. I was waiting for you to tell me.”

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))

Mr. Al Pete and Notsucal Release Their Latest Collab, ‘G4.5’

Dinner Party, Tom Misch and More from the Neighborhood with Mr. Al Pete

An Ultra-Chill Playlist from the Latest Episode of Electro Lounge

Sing Out Loud Festival Returns With Hozier, Beabadoobee, Father John Misty, Vance Joy and More

Chicago Alt-Country Faves Wilco Return to St. Augustine with Indie-Folk Great Waxahatchee

Looking for an Alternative to Spotify? Consider Hopping on the band(camp) Wagon

Khruangbin to Bring ‘A LA SALA’ Tour to St. Augustine in April

Perfume Genius, Flipturn, Tamino + Mitski and 6 New Songs to Stream

Song of the Day | “all tied up” by Glixen