You might not know his name, but if you’re a performer or fan of the Northeast Florida music scene, you’ve heard the sound or felt the presence of Roy Peak.

A decades-long participant in whatever alt-music scene that Jacksonville has had, Peak is a bassist and song-songwriter, as well as an in-demand sound engineer-producer (doing live sound for musicians including L7, the Dead Milkmen, Corrosion of Conformity and John Lee Hooker) and is also the author of short fiction and music criticism. As the bass guitarist of local bands including 86 Love, Nerve Meter, The Problems, Radio Berlin and Soul Guardians, Peak has been a ubiquitous figure from the early-’80s days of the beaches punk-dive the Blighted Area, a regular onstage at the all-ages club Einstein A Go-Go, to being the longtime sound engineer at the Riverside Arts Market.

Peak’s roots dig deep, entrenched in a scene of more seasoned players who are as diverse as his creative output. Over the decades, Peak has worked with scads of area musicians including snarling rocker Thommy Berlin, urban-folk singer-songwriter Lauren Fincham and rootsy singer-songwriter Mark Williams; in recent years, Peak has played bass guitar with Robert Lester Folsom, who has enjoyed a rightful revival after a late-career appreciation of Folsom’s 1970s DIY albums. If there’s aesthetic common ground amongst these players, its arguably a collective infinity of informed eclecticism, musicians who find inspiration from both the New York Dolls and Laura Nyro, the MC5 and Joni Mitchell.

These kinds of long-term relationships seem key to Peak’s approach and all three of the aforementioned players make guest turns on Peak’s latest full-length release, Exile in Americana.

Clocking in at just over an hour, Exile features 18 originals, some co-written with Peak’s peers. The songs sound wrapped in grit, faded Duval denim, jubilation and loss. They have an off-the-cuff vibe that points to what they are: a group of musicians of the same overall generation who find camaraderie in songs expressed through frills-free rock. The songs on Exile include ballads and bar-room rockers, with instrumentation favoring acoustic guitars, a solid rhythm section, pedal steel and six-string solid-body crunch, and Peak’s lead vocals, which boast a road-worn quality that favors emotional growl and punky sneer.

“As Liz [Phair] named her album after a place where she felt alienated, I did the same. I still think of myself as a punk rocker, but never quite fitting into either category.”

Roy Peak

The Jacksonville Music Experience reached out to Peak to ask about his inspiration and motivations for creating Exile in Americana. We also talked about his music career, one that seems more intent on cultivating and sustaining creative relationships than chasing music trends and pop-music recognition.

You have described Exile in Americana as being a song-by-song commentary on Liz Phair’s 1993 album, Exile in Guyville, which in turn was a type of conceptual response to The Rollings Stones’ 1972 album, Exile on Main Street. What was it that you found so compelling about Phair’s album that led to you structuring your album as a response?

I loved Liz’s album the first time I heard it. I appreciated the nod to Exile on Main Street, but also how Liz’s album stood on its own terms. You needn’t any prior knowledge of Main Street to enjoy it, and I was mesmerized by the lo-fi production—almost akin to a demo, which I adored—Liz’s carefree vocals, and such great songs. I was inspired from the first listen.

While working on my album—originally to be titled More Songs About Love, Death, and Birds—I started to wonder if anyone had already done a response to Liz’s album, and when I searched on the internet and found out that no one had, I decided to just go for it. Of course, not every song I had already recorded fit the format, but enough of them did fit surprisingly well. I knew that I would have to write another batch of songs and quickly got to work.

Are the songs on Exile in Americana all an exact response or commentary on the song sequence of Exile in Guyville?

For the most part, yes. For a few songs I had to go back to the Stones’ album to get a sense of how Liz was responding to their songs. The first song on my album, “Biting Off More Than I Can Chew” was a direct response to how I felt taking on this huge task: I’m speaking directly to Liz, saying thank you for your songs, here’s mine. “The Fisher King” was a response to her song “Dance of the Seven Veils.” I decided to keep the historical influences and wrote a sort of love song around the theme. “The Ballad of the Legendary Elvis Kabong!” was written before this project, but not one I had ever planned on recording. I was in a band called Elvis Kabong and wrote this song about that, only as if it were a cartoon show. I needed a song that matched up with Liz’s song “Soap Star Joe” and “Kabong” was perfect, so I recorded it right away.

I personally still cringe a bit when I see the term Americana, as it could denote music as far afield as Elizabeth Cotton and John Fahey, the Fugs and Lucinda Williams. The facets, instrumentation and approaches that invoke or pay tribute to “traditional American music” are incredibly varied. What are your thoughts on the Americana category and how do you personally define it?

I’ve never cared for that term much, but it’s become the placeholder now for so much music, even from many musicians who’ve never even set foot in America! When I first started releasing my own music years ago, I was lumped into the “Americana” category automatically, I’m assuming because I’m rough around the edges but use a lot of acoustic guitars and some pedal steel. As Liz named her album after a place where she felt alienated, I did the same. I still think of myself as a punk rocker, but never quite fitting into either category. Roots Rock? Alt-country? Americana? Who knows? And like I say in one of my songs: “It’s punk rock in the summertime, Americana in the fall, call it what you like, It’s all the same damn song!”

The common denominator of Exile in Americana is you—what was the process and criteria like for essentially curating your collaborators, and mixing and matching the specific musicians for specific songs?

I’m lucky in that I know a lot of excellent local musicians and was able to handpick who I felt would be best for each song. Nobody does incendiary screaming, noisy guitar like Thommy Berlin, so that was an easy pick. Brian Homan is a world-class pedal steel player always up for a challenge. Mark Williams and Lauren Fincham are both excellent guitarists and singers, so having them be able to do both was a timesaver. I also played many of the drum tracks myself, but whenever I found a song that I couldn’t do justice to, Sean Jones stepped in and knocked it out of the park. My original plan was to have some friends I know from outside of Jacksonville play on a few tracks, but my local base of artists seemed to cover everything just fine.

The album features a diverse roster of local collaborators, including Lauren Fincham, Thommy Berlin and Robert Lester Folsom, to name just a few. Considering your ongoing musical and personal relationships with many (if not all) of the players involved, did that familiarity and history ever create any unexpected challenges?

I’m lucky in that I haven’t burned too many bridges amongst my fellow musicians and so have a strong core of talent to pick from. The most difficult part was deciding on who wouldn’t be on a particular song. As they’re all excellent musicians, any of them could have played something fantastic that would have worked. I was lucky in that they were all able to make their time available to me and that we’re still friends even after all my crazy and demanding requests while in the studio.

Have you made any attempts at trying to get the album directly to Liz Phair or do you plan on trying to make her aware of it?

I sent the press release to her record company but have heard nothing back. I considered tagging her on social media, but wanted to wait awhile, to let the album breath on its own. I would love to get her reaction—will she love it or hate it?

How long did the album take to complete, from its inception to fruition? Did you have a set number of songs or did you have to narrow down a larger pool of contenders of the record?

I started this in late 2021 and finished it early 2024. I started out with twelve songs for the earlier version of the album, but only eight of those really “plugged in” to the format for Liz’s album. I found out that writing songs that were good responses to Liz’s songs was not easy. I threw away about twenty songs in the writing process to come up with the right material to satisfy me. I also revisited several earlier songs I had written, mining the discard pile for anything that fit. “All the Birds of Carmelita” was released as a demo on a compilation album years ago, but after a few other songwriting attempts fell flat, I decided that it was a great fit for Liz’s song “Flower.” As a past middle-aged man I’m positive I couldn’t pull off something as sexually charged as “Flower” so I went with a person obsessed with changing something in their life—what I found to be the core of what Liz’s song was about. Liz was making a bold statement, so I did the same. This was also why I matched up “Three-Chord Criminal” with “F*ck and Run.” She’s making a bold personal statement, I wanted to do the same. “Glimmer” was written ten years previously, but I felt compelled to use it to match up with Liz’s song “Shatter” If you know enough about Mick and Keef, you can probably figure out why!

How do you write music: Do you sit down for a fixed amount of time and not quit until you have written a viable structure of a song or do you write simply when you suddenly have an idea and the muse arrives?

Actually, a little of both. Usually I only start a song when the inspiration strikes, whether a few choice lines, or an intersection chord progression. Sometimes these are written in minutes (as in the case of “Biting Off More Than I Can Chew,” and “The Fisher King”) but others take months (“Waiting on the Rain”) or years (“Three-Chord Criminal”). “Annus Horribilus” was inspired by a conversation with Lauren Fincham about Queen Elizabeth’s speech in 1992. It was a horrible year for the royal family, and coincidentally, of us also and several of our friends. Relationships floundered, our band broke up, jobs were scarce, our lives were in a tizzy. I wrote a couple of verses, she suggested using more of the burning castle imagery, and a song was born. She played the finger-picked distorted electric guitar throughout the song and added background vocals as well.

You’ve been involved in the Northeast Florida music scene since the ‘80s (that I know of); what are your thoughts and even criticisms of how the area’s music community has changed?

I first hit the scene in 1983, playing in a few bands that went nowhere fast. The scene at the time was mostly southern rock, country music, or metal bands. A lot of the clubs were very hard to break into if you weren’t part of their clique. “How many Skynyrd songs do you play?” was something we heard too many times. “If you don’t play any Skynyrd, you ain’t gonna play here.” When the so-called indie scene started happening it felt combative and very much dog eat dog. Very few bands supported one another, there was a lot of jealousy and backstabbing going on, and still very cliquey. Thankfully, this has changed dramatically. The scenes (so many little disparate music “scenes” in this town) are much more supportive, overlapping, and constructive nowadays. There’s still work to do, but it’s much more pleasant to work in this town than it was three or four decades ago.

You work with many peer-musicians who are of roughly the same age; considering that music (and culture) celebrates youth in such an emphatic way, do you think there’s an ageism towards older musicians?

I think that there used to be. I work with many musicians of all ages, and it seems as if the younger ones, just starting out, have more reverence and respect for older musicians nowadays. When rock music was young, it had to fight against the old guard to make its mark. Now the younger artists of today are looking back to the ones who came beforehand, learning how they crafted their art and building on that, instead of tearing it all down and starting from scratch. This might go against the grain of “rock ‘n’ roll rebellion” but it’s not a bad thing for sure.

Edited for content and clarity. Exile in Americana is now streaming and available at Roy Peak’s site.

Mr. Al Pete and Notsucal Release Their Latest Collab, ‘G4.5’

Dinner Party, Tom Misch and More from the Neighborhood with Mr. Al Pete

An Ultra-Chill Playlist from the Latest Episode of Electro Lounge

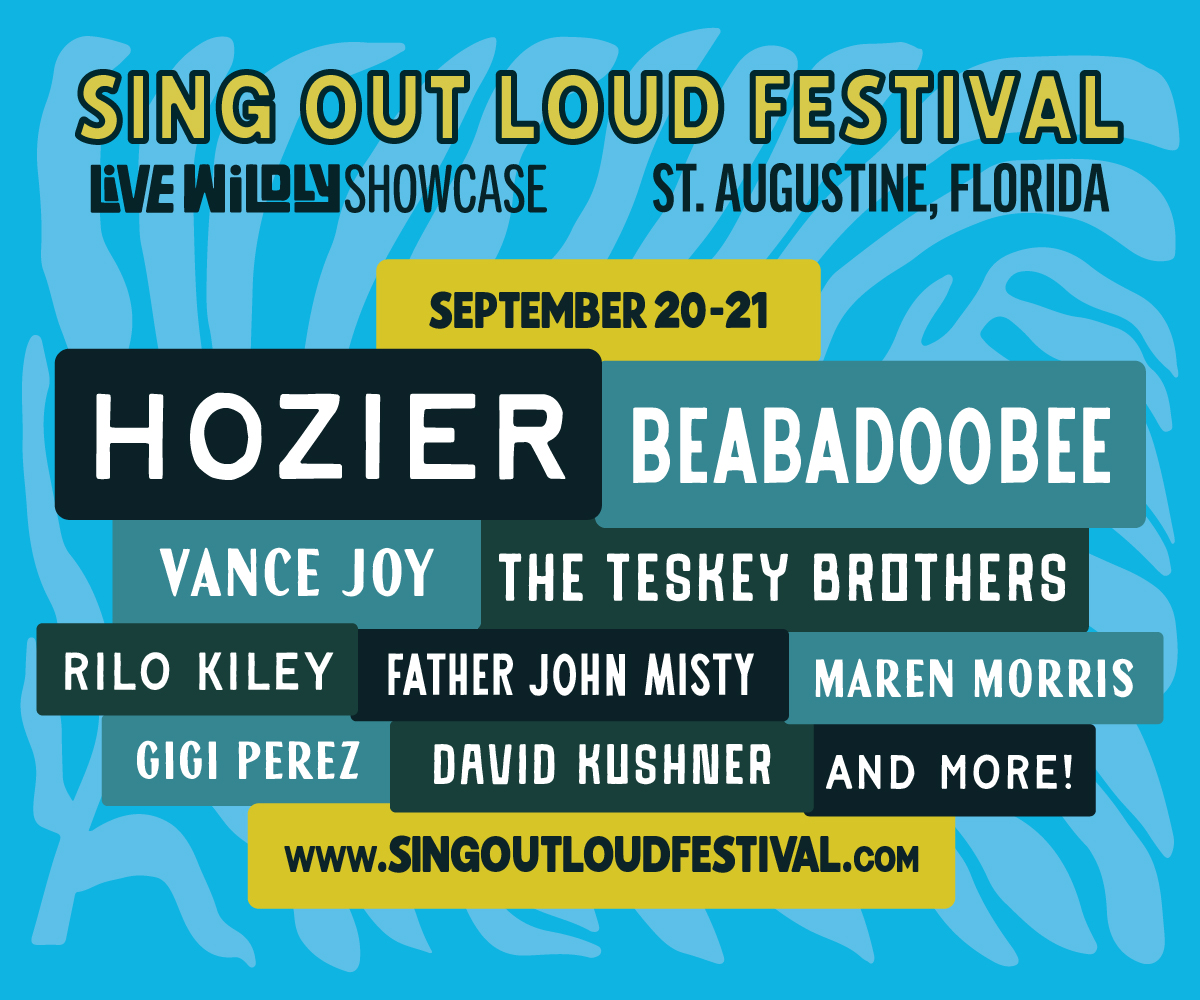

Sing Out Loud Festival Returns With Hozier, Beabadoobee, Father John Misty, Vance Joy and More

Chicago Alt-Country Faves Wilco Return to St. Augustine with Indie-Folk Great Waxahatchee

Looking for an Alternative to Spotify? Consider Hopping on the band(camp) Wagon

Khruangbin to Bring ‘A LA SALA’ Tour to St. Augustine in April

Perfume Genius, Flipturn, Tamino + Mitski and 6 New Songs to Stream

Song of the Day | “all tied up” by Glixen