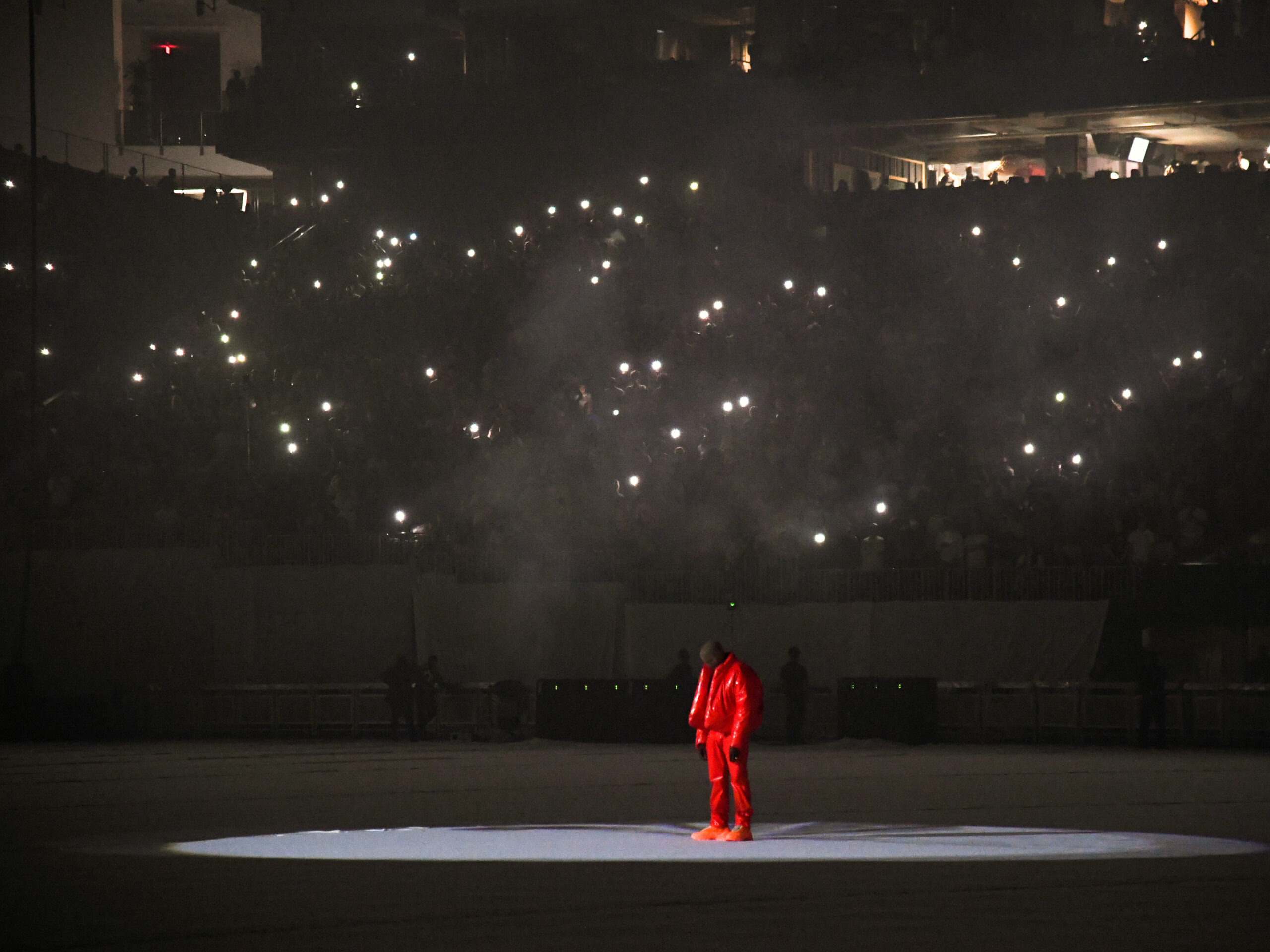

While recording Donda, Kanye West paid $1 million per day to live in the belly of Mercedes Benz Stadium, in a stuffy room that resembled a jail cell. As with his last several records, his hulking new album arrived in fits and starts, like a lawnmower revving up for three weeks. Three stadium listening parties – two at Mercedes-Benz Stadium, one at Soldier Field – brought millions of viewers into his process. If you tuned in to the livestreams, you heard scratch vocal takes, you heard verses added and dropped, mixes fine-tuned, tracks moved around the sequencing — Did he really replace Kid Cudi with Globglogabgalab? You saw Kanye West ascend like an angel, light himself on fire, do pushups, dance in a spiky suit. You saw Dababy and Marilyn Manson, fresh off homophobic comments and abuse allegations, respectively, emerge from a recreation of Kanye’s childhood home. You never saw Kanye’s face. And then, maybe, you gave his new album a spin. Price of admission for listening to the record: nearly two hours of your time.

Donda is Kanye West’s tribute to his late mother, Dr. Donda West, an academic who loomed large over his life as not only a guardian but also a musical advisor (Kanye has described her as his “momager.”), and who appears for a sole interlude here. (She was featured on several more tracks in an earlier version of the album.) But this album is mostly about Kanye – his continued reckoning with his faith, his relationship to the music world, the end of his marriage to Kim Kardashian. Many of the songs that sustain these ideas sound cobbled together in the last few weeks.

The issue with his recent music is that of late, Kanye’s process has stymied his biggest ideas. He seems to draft songs around shifting album release dates instead of fully-realized artistic visions. He scraps whole albums and then churns out new ones in a couple weeks. He works in big bursts of creativity, makes calls to Rick Rubin at the eleventh hour, has fans worried he’s not letting Mike Dean sleep. Since the excellent Yeezus, the albums have come out messy and bloated, like 2016’s The Life Of Pablo, or slight and half-finished, like ye and Jesus Is King. This quality control issue also plagues Donda, a gargantuan album full of gestures at interesting music, that rarely sticks the landing on any of them.

Incidentally, the last time Kanye wrote an album tied to his mother was his first foray into a frenzied recording process. During the Glow In The Dark tour, the one with the spaceship and N.E.R.D., the rapper began to explore bending his voice with pitch-correction technology, initially so he could sing T-Pain’s chorus on “Good Life” live. Then, between tour dates in the fall of 2008, Kanye recorded 808s & Heartbreak in three weeks, a vessel for his emotions boiling since his mother’s death and breakup with his fiancée. He premiered the single, “Love Lockdown,” on his blog, then tweaked it days later based on negative fan reception.

“Your prayers have been answered!” he wrote on his blog. “There’s a new version of ‘Love Lockdown’ coming. We used new taiko drums and I re-sung it… it’s being mastered now … “

808s was loaded up with dejected pop hooks and a chilly sonic palette. It opened with a song that flung fantasies and crash-landing lovers through cold Auto-Tune, then stretched out with a haunting wordless choir for several minutes. That outro to the intro is one of Kanye’s best and most indulgent, earned through piercing songwriting and textural study.

A similar meandering choir outro returns on Donda, on the song “God Breathed.” By comparison, it functions more like melatonin. It follows a limp, dancey bassline, a chopped vocal sample, the singer Vory crooning like a frog and Kanye rapping in clipped, unmusical phrases, proclaiming that “God breathed on this.” It is frustratingly bad.

Over the last several years, Kanye’s sound has approximated a kind of hollow excess, defined by epic chord progressions, minimal drums, head-turning guests and scorched synth lines with little in the way of solid rapping. Donda‘s lethargic sequencing reveals how these prestige-rap cues are not always a formula for good music. Across the first half, we sit through moments of magic — the operatic “Jail,” Young Thug’s slinking verse on “Remote Control” — and earsplitting failure — Jay-Z’s verse on “Jail,” the lifeless “Ok Ok.” Much of Donda is a weak amalgamation of several bygone eras of Kanye; the buzzing stomp of “Heaven and Hell,” for instance, aspires for grandness and intrigue a la “Flashing Lights,” but comes off more as self-parody. These songs are almost predictable: Insert beat switchup here, insert rolling guitar solo there. Many of them feel empty, like Silicon Valley aphorisms or the concept of “free thinking.”

What sets Donda apart from recent Kanye releases (beyond being 35 minutes longer than the last three combined) is that it seems destined for radio play. However, unlike the Kanye of a decade ago, Donda-era Kanye conforms to the rules of radio instead of writing them himself. The fan favorite, “Off The Grid,” transforms into a roaring Brooklyn drill track midway through, featuring a charged-up Fivio Foreign powering through a melodically complex bassline and sustained choir. But part of the appeal of drill is the way it conjures grandness through fine-tuned skeletal elements and negative space – “Grid” overcompensates and, consequently, comes off as flimsy. (Speaking of Brooklyn drill, with its plodding piano instrumental and lack of drums, the Pop Smoke-featuring “Tell The Vision” must be one of the worst pieces of posthumous rap I’ve ever heard.)

The strongest piece in this convoluted musical puzzle is the organ, which shifts from its small role on Jesus Is King into a powerful complement to Kanye’s voice. On the glorious gospel cut “24,” Kanye sings confidently and endearingly off-key, conversing with the organ stabs with the soul of a seasoned vocalist. And “Pure Souls” partners Kanye with Roddy Ricch for a bouncy, organ-driven collaboration that feels like a righteous update to Pablo standout “Highlights.” When Kanye sings, “This the new me, so get used to me,” the proposition doesn’t sound too bad, for a moment.

Unfortunately, the “new me” is otherwise indulgent in service of nothing. Kanye’s explorations of faith are slightly more nuanced than they were on Jesus Is King, but they aren’t particularly profound. (“And I don’t do commercials, ’cause they too commercial / Give it all to God and let Jesus reimburse you,” goes one clunker.) Donda pushes out an army of guests so large that on some songs, like the sleepy, Lil Durk-assisted cut “Jonah” and the Griselda posse cut “Keep My Spirit Alive,” you don’t hear Kanye’s voice for the first few minutes (and on others, he’s not even present ). Every Kanye album is communal, but this is the first to consistently drown out Kanye himself.

Maybe that’s a good thing. The problem with every Kanye album since Pablo has been Kanye. He has turned into a genuinely awful rapper, incapable of finishing a verse without saying something unforgivably dumb or running out of steam mid-take. His arrhythmic word vomiting worked occasionally on Pablo, like on “No More Parties In LA,” because it served the broiling anxiety in his writing. But almost every time he raps on Donda, it sounds like he’s relearning how to flow and stay on beat. The most damning example here is “Jesus Lord,” wherein Kanye fumbles what could’ve been a staggering story rap, stumbling through breathy, punched-in takes, forgetting to rhyme sometimes and slowly eking out bars like, “I’m just reaching for the stars like Buzz Lightyear.” Moments like “Lord I Need You,” where Kanye raps competently and humorously describes his former marriage to his ex-wife as the “best collab since Taco Bell and KFC,” are few and far between.

Donda treads prog-rap water for most of its runtime, but reaches a moment of transcendence near its close. The song “Come To Life” pushes Kanye’s voice and spirit to their limit. He sings, beautifully, about wanting another life, and describes his relationship to Kim in that classic, almost Broadway manner that only he can: “I get mad when she gone / Mad when she home / Sad when she gone / Mad when she home.” As those piano keys tumble and he describes “floatin’ on a silver lining,” you can almost visualize him ascending out of that bunker, out of that stadium, into whatever freedom looks like for Kanye these days. Then you remember that he did all that for this deflated balloon of an album, and Kanye comes hurtling back to Earth.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))

Mr. Al Pete and Notsucal Release Their Latest Collab, ‘G4.5’

Dinner Party, Tom Misch and More from the Neighborhood with Mr. Al Pete

An Ultra-Chill Playlist from the Latest Episode of Electro Lounge

Sing Out Loud Festival Returns With Hozier, Beabadoobee, Father John Misty, Vance Joy and More

Chicago Alt-Country Faves Wilco Return to St. Augustine with Indie-Folk Great Waxahatchee

Looking for an Alternative to Spotify? Consider Hopping on the band(camp) Wagon

Khruangbin to Bring ‘A LA SALA’ Tour to St. Augustine in April

Perfume Genius, Flipturn, Tamino + Mitski and 6 New Songs to Stream

Song of the Day | “all tied up” by Glixen